In 1993, a clothing brand called Poot! was trademarked by Tod Swank of Foundation Skateboards intended for a female market thanks to a connection with Keva Marie Dine the previous year. Keva Marie would become the lead fashion designer and visionary behind Poot! and the Foxy fanzine.

For PAPER magazine, Keva Marie explained that “It was so obvious to us that girls should have something of their own. They hung out at skate shops, bought boys clothes. It was just screaming at me. But people thought it was really funny at first and wouldn’t buy it. We had to convince shop owners that they would meet more girls if they had these clothes.”

Before delving into Poot! some historical context needs to be in place. In the 1980s and 90s, skateboarders, regardless of gender really struggled with their sense of identity and authenticity. It was a time when someone could be quickly labeled a “poseur” for being a beginner or for wearing skateboard brands without actively skating, and if you were a girl on the perimeter, you could be dismissed as a “pro ho” since “pros” were obviously only men!

The 1990s was also an era rooted in misogyny. In the media, women were often sexualized for the benefit of heterosexual men and dismissed rather than portrayed as legitimate members of society, which also meant that the concept of “consent” was barely understood.

In the skateboarding community, board graphics and advertisements often reflected the sexist values of dominant society, and girls and women were not encouraged to participate, and would generally be taunted and mocked if they tried. And if, like Elissa Steamer they were competent and received sponsorship, the mainstream male-dominated scene viewed her as a threat and condemnation came in the form of hurtful speculation around her gender and sexuality. There was still a huge stigma in being deemed a lesbian or queer, and this labeling was an attempt to deter young women from taking up sport, especially skateboarding.

In some ways, Poot! was an invitation to girls to simply be part of the skateboarding community, and a reminder to men that women should be respected as friends and partners, rather than mocked or hated. It was a “start small” approach. Introduce the idea that girls exist in relation to skateboarding, and that they may be a market worth catering to, which was hard for many skateshop owners to grasp. And maybe, some of these girls would rally together and actually try to skate.

But because Poot! was technically overseen by men, there was some skepticism about their motives by female skateboarders who had already made the move to defy the norm and skate, unlike a brand like Rookie Skateboards which emerged a few years later. I would be hesitant to say that Poot! paved a path for women’s skateboarding brands because it never actively sponsored girls as skateboarders, but it was a reminder that women have a presence and could be tapped as a market.

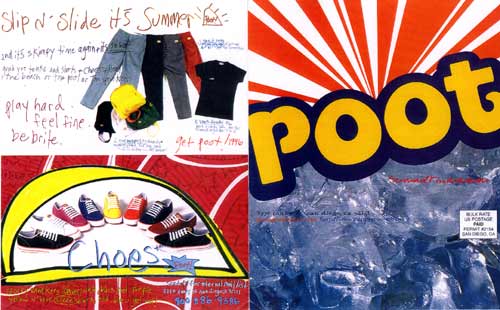

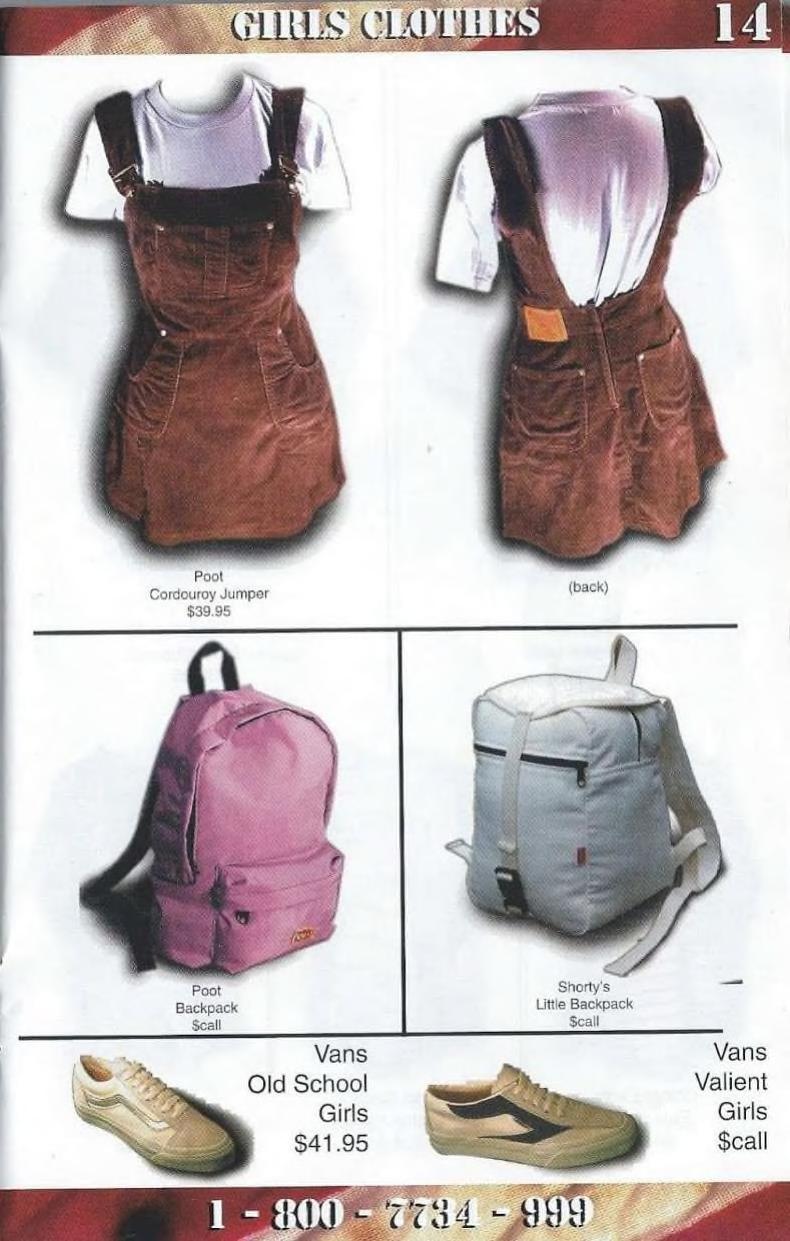

Photos: Poot! products from the “Church of Skatan” Summer 1995 catalog

Being a “market” that men want to target is problematic though because they often want to manipulate the market rather than listen and adapt. For example, in the 1990s (and earlier), if a sporting brand wanted to include a female athlete on their roster, the individual would often be paid drastically less than a male peer and pressured to project a feminized heterosexual appearance to appear less threatening. Even Vanessa Torres reported on experiencing this pressure in the early 2000s with her sponsor Element.

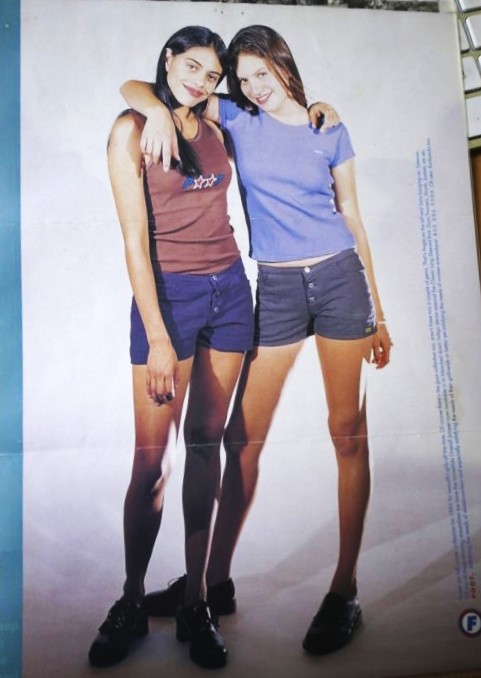

As a result, Poot! seemed to fall under the umbrella of being a brand that pushed a feminine style that was an acceptable and “cool” image for a heterosexual girl, who was adjacent to skateboarding to wear, but not necessarily as an active participant. There’s nothing wrong with skateboarding in tight crop tops or skirts, and compared to a Hubba wheels ad, Poot! was mostly fun and cute. It’s just problematic when a girl is told that one style represents heterosexual, and a baggier sporty style represents homosexual, and is equated with being wrong or shameful.

Thankfully, this equation relating to one’s sexuality based on clothing is no longer really a debate. Clothes are not a direct indicator of sexual preference, and the individuals (and politicians) who do try to stigmatize LGBTQ2S+ people are obviously miserable, ignorant haters, unworthy of anyone’s time or consideration. Clothes are just clothes.

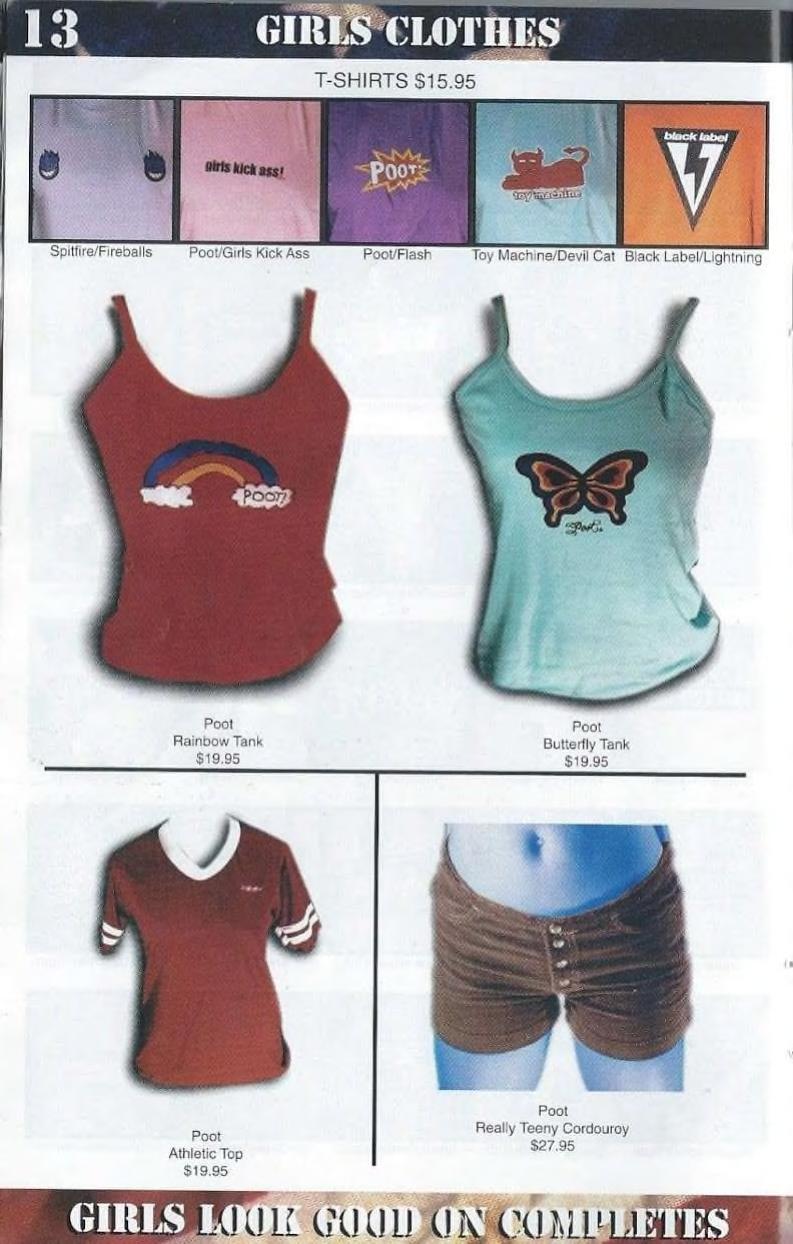

Photos: Poot! products from the Winter 1995 CCS catalog

An in-depth article about the brand and the role of Keva Marie, was written by Sarah Huston for YeahGirl in 2020, exploring the company’s impact. Huston wrote, “What began with a simple Poot! t-shirt graphic grew into a full cut and sew range, a shoe line (Choes), and full-color magazine (Foxy) – all for girls. For such a pioneering brand, it’s a wonder that so little is known about it now.” Keva Marie then shared how she was living in Solana Beach in San Diego, taking classes on fashion and marketing at college and had actually produced several lines of clothing throughout her teen years leading up to Poot! which was conceived in 1991 when she was age 21.

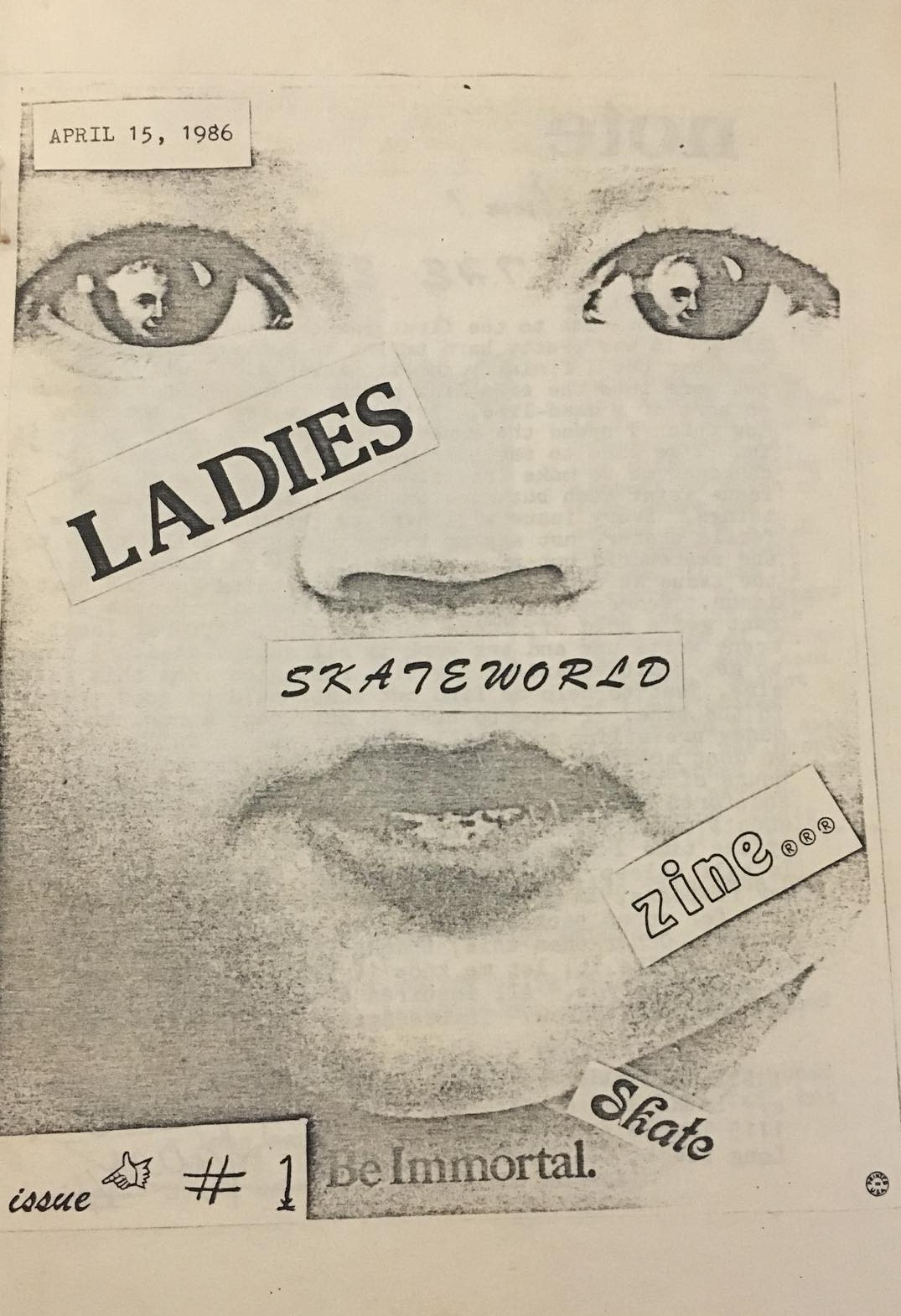

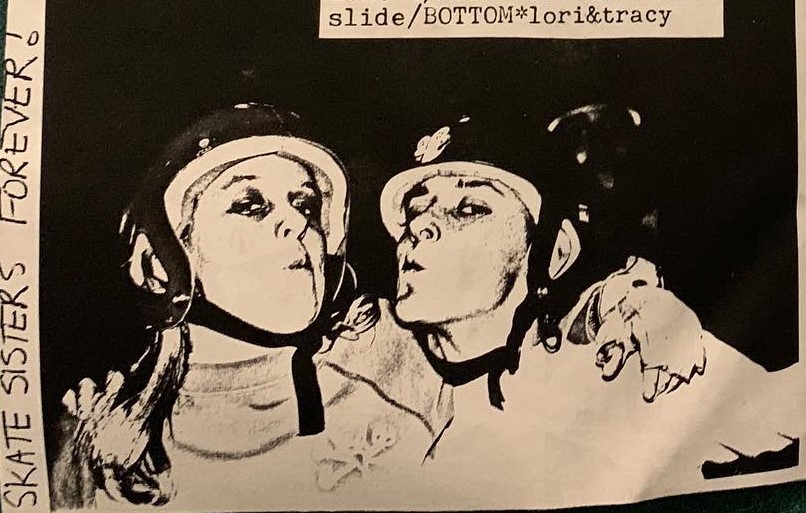

Skateboarding was on Keva Marie’s radar but only superficially since “My best girlfriend and I, Tricia Kay-Fambro used to go to the Del Mar Skate Ranch and jump on the trampolines and watch her cousin Rex Kay (RIP) and all the boys skateboarding.” Unfortunately, Keva never met any of the girls skateboarding at Del Mar like Lori Rigsbee and Lauri Kuulei Wong who produced the zine Ladies Skateworld in 1986, featuring her friends like Ericka and Rhonda Watson.

The connection with Foundation skateboards was due to Keva’s boyfriend, Greg Goodfellow who was on flow for the company, and introduced her to the owner Tod Swank while visiting the warehouse, who noticed Keva’s appreciation for fashion. “Tod was interested in getting into clothes – like actual cut and sew pants and stuff – and I knew girls clothes… I also knew about marketing, and I had the energy and I was just really into it.” Keva and Tod motivated each other, and Tod already had the name Poot! picked out. “It means farting which I thought was kind of crass and he was like, yeah but, you know… skateboarding.”

Huston mentioned that the story of Poot! was hard to unearth, with only random mentions on the Slap message board, sometimes with gossipy intent related to Keva and Tod. I was able to find two polar opposite reviews of Poot! starting with a letter in the Maildrop section of Thrasher from February 1996 by Barbarann Kymm of Seattle, WA:

“I am sublimely fond of your magazine except for its sexist content towards women. Women are presented more as tools, objects, ultramasculine, virile collateral. I am a female skater, and I find some of your ads as well as reading content to be demeritorious. I am especially disgusted with your “Poot” ads. They (the items of clothing) are nothing more than too-tight, overpriced, trendy pieces of shit. I always see girls hang out at the Sea-Skate (in Seattle), wearing those Poot-inspired clothing articles. They don’t even skate.”

Poot! emerged during an era when the Riot Grrrls were beginning to voice their disdain for sexual harassment and alienation in the punk scene, while condemning the corporatization of their movement which became a gimmick known as “Girl Power.” The intentions of Girl Power were capitalist, under the guise of preaching women’s empowerment. And yet, as Keva Marie acknowledged in an interview for PAPER magazine, Poot! was different from a previous attempt to cater to women by VisionWear since “they made this stuff out of spandex. It was a different kind of girlwear, if you know what I mean.”

To someone like Barbarann, Poot! seemed to be catering to the male-dominated community, rather than seeking to elevate female skateboarders. Part of this skepticism was the company’s allegiance to Big Brother and TransWorld magazines, which did very little to support female skaters. The strategy was more about getting the approval of male skateboarders (ie. the Ronnie Creager ad that announced Poot in the small print – for “the girlfriends”), that they should be attracted to girls who wear this brand, and therefore, girls who may be isolated or on the outside looking-in would buy the brand to feel accepted.

On the plus side, Poot! and Foundation definitely had a safe sex outlook (there’s a photo at the Foundation warehouse of Keva Marie and friends stuffing condoms into the pockets of pants), but this would be marketed for heterosexual sex only.

The marketing tactic worked and there was a growing following of young women that Keva Marie fondly called “Poot! Girls,” several of whom featured in their ads. Without knowing the individual models, it’s hard to say if they were being empowered or just conforming to what a male ad designer wanted, but Poot! was not alone in this trend.

Keva noted that she was proud that Poot! came before another brand rooted in the music industry called X-Girl (associated with Kim Gordon, Daisy von Furth, Sofia Coppola, alongside Spike Jonze and the Beastie Boys). See the MTV video from April 1994 of their X-Girl street fashion show.

There was even a Poot! commercial in the 1994 Foundation skateboarding video called Tentacles of Destruction featuring a girl named “Lauren” that was commended for being sexy in the December 1994 issue of TransWorld. The ad appears at 14:45 of a 25-minute video chock full of dudes skateboarding. Lauren prances about in her skirt and Poot! clothing and appears cute and vulnerable. It’s not offensive, it’s just not bold and it subtly makes sure that girls know their place in the hierarchy.

Keva Marie did recognize the power imbalance in the skateboarding scene. She said, at the warehouse, many of the male skateboarders “didn’t really like me. They were like, why are you here? Why am I taking direction from you? You’re just a girl. But there I was working double shifts, designing pants for the guys, and the Poot! tees and hot pants, and creating ads with Tod. I had a mission, but it still was bad vibes for a while… They would just walk away from me and not even engage in conversation. I was just not accepted.”

It’s curious that Tod and Keva Marie felt that they had to distinguish between their girl brand and their boy brand, and that skateshops were reluctant to include the “girl brand” within their store. But in the 1990s, everything was so black and white. Many people couldn’t conceive of the idea of just creating smaller clothing that a girl could wear because then she would be seen as some kind of cross-dresser pushing gender boundaries. An appreciation for female skateboarders as a legitimate market has only really solidified in the last five years, and several brands are finally going gender-neutral in their sizing rather than aligning with binary divisions.

Keva Marie still felt a feminist calling to make a gender distinction with Poot! and at least it was a reminder that women existed in relation to skateboarding. And the brand was successful. Keva Marie said, “I saw all these girls that weren’t being represented and I wanted to give them a movement and their own thing. I was like, we’re here too boys! We had buying power and we wanted to wear cute stuff and be part of this scene.”

Huston then asked Keva Marie if Poot! had a skateboarding team but long answer short was no even though in her PAPER interview, there was mention of girls receiving skateboards. Poot! was more about acknowledging the girls on the periphery like artist and photographer, Deanna Templeton, who didn’t skate, but was respected for her creativity and being the girlfriend of pro skateboarder, Ed Templeton of Toy Machine. Perhaps, being in the vicinity of strong women at least made the idea of sponsoring Elissa Steamer an obvious option for Ed and Toy Machine?

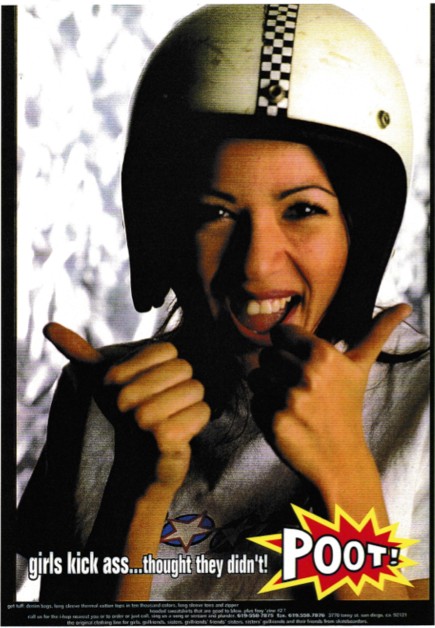

In fact, it was Deanna who came up with the Poot! campaign that said, “Girls Kick Ass” or G.K.A. after seeing the Toy Machine stickers that said, “Skateboarding Kicks Ass.” The intention was good, and the campaign was a success, but it still separated “girls” from “skateboarding” rather than building approval and acceptance for girls to take up skateboarding.

The Poot! Girls Kick Ass ad appeared in TransWorld magazine (July 1996 p145). Keva Marie regarded it as a statement of solidarity.

Deanna and Ed Templeton would document not just skateboarding culture, but American youth culture, and kids living on the margins. Deanna’s photography was on par with Ed, and they would often collaborate on zines and exhibits. Although there was a special exhibit called Spectacle at L.A.’s Millicent Gallery (May to June 2004) featuring 12 women who had met through skateboarding including Deanna, Angela Boatwright, Lisa Whitaker, Luciana Ellington (Toledo), Ana Paula Negrao, Jessie Van Roechoudt, Desiree Astorga, Jardine Hammond, Saba Haider, Sharon Tomlin, Cel Jarvis, and Bethany Black.

Photo by Deanna Ellington from 1998 of the skateboarding artist Margaret Killagen (RIP) and an article reflecting on the Templeton’s relationship and connection to Margaret.

Calling Poot! a skateboarding brand is problematic, but it was a challenging time, and I don’t doubt that many of their target audience likely wanted to take up skateboarding or at least wanted to feel part of an alternative community that was a little edgy and cool.

There’s a great testimonial in the fashion blog STOPITRIGHTNOW from 2009, regarding Poot! The author had been taught to sew by her mom and grandma, who was a skilled seamstress. And “as i grew older i became more preoccupied with the surf and skate world… the only new clothes i found myself buying were skate brands. my TSA tee and Fuct tee were on rotation all through the week, but my all time favorite brand was Poot.”

The author even worked at what she considered to be a girls’ skateboard shop, located a floor above the actual local skateshop in Newport Beach (again the separation), which would need verifying, but Poot! was the brand that influenced her the most. She embraced the “messages of women’s empowerment without all the gnarly bra-burning hardcore feminist vibe… i read Foxy like it was my bible.” To this individual, Keva Marie and Deanna Templeton were her idols and Poot! made her feel accepted as a girl who loved skateboarding and just wanted to be part of the scene, yet not aligned with someone she might dismiss as a pro ho “jocking the dudes.”

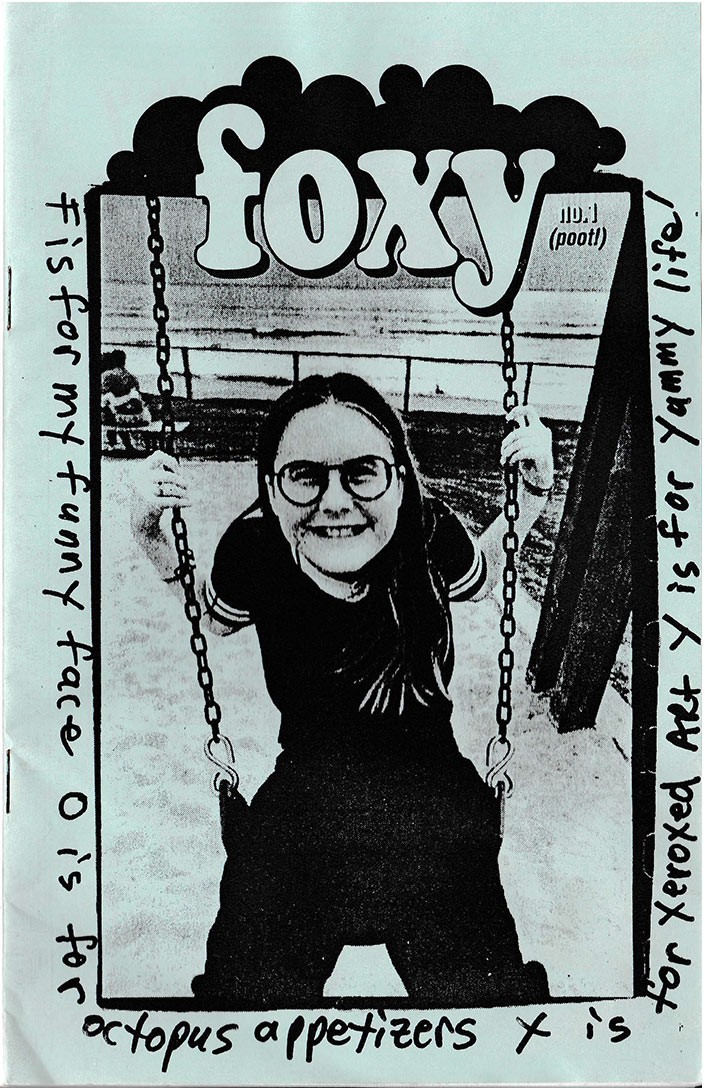

Keva Marie was savvy to recognize the importance of community and ended up channeling a DIY spirit to create her zine Foxy in 1993 based on the fan mail she was receiving, including photos of girls wearing Poot! product. She said, “Tod was also in the zine scene [Hot Rod, Swank Zine] so it might have been his idea, but we just took all of these letters and instead of writing everyone back we made these black and white zines on the Xerox machine and sent it back to everybody.” The photos also made their way into ads with their “real girl model search.”

The name Foxy was a kind of spin-off to Sassy Magazine with dating advice, fashion shoots, letters and photos. Keva Marie wrote on her website that while Foxy was originally a Poot! fan zine, “it didn’t take long for FOXY to grow into a cult favorite among the girlie set and the teen girl magazine world.” Foxy was a black & white format for three issues and then evolved into an online platform.

Keva Marie shared that Clea Hantman was hired as a writer and Miki Vuckovich, a skateboard photographer, was hired for photo shoots. When they went online in 1994, Wired magazine took notice and did a feature on their “web zine” as a new online concept for teenaged girls, interviewing Keva and Clea. The print issue evolved in a color magazine for four more issues and was distributed not only at skateboard shops but fashion outlets like Urban Outfitters worldwide.

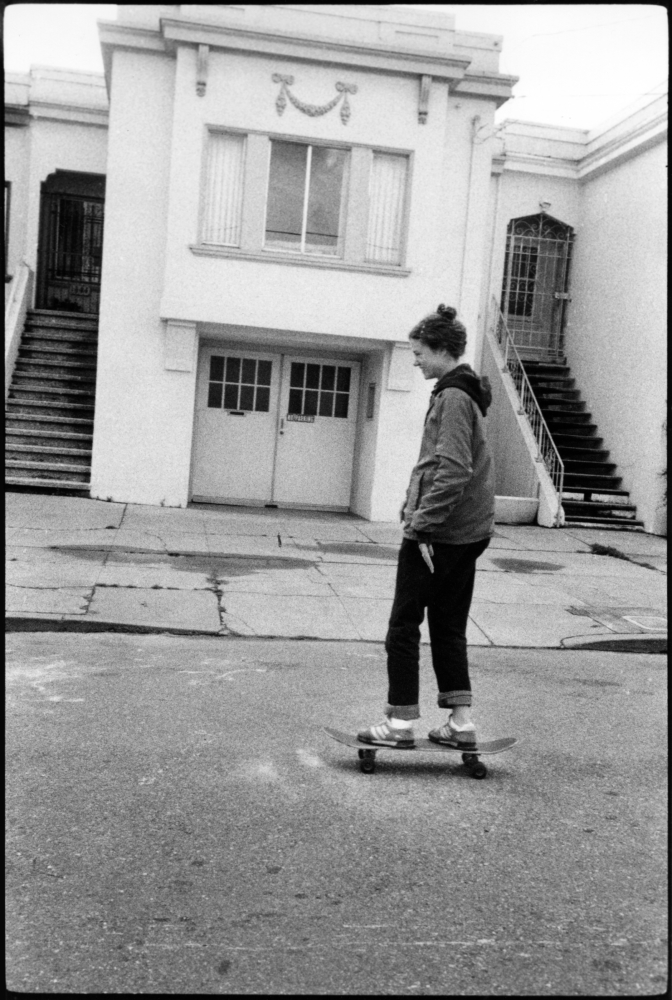

I was grateful to see that in Issue 5 of Foxy an active female skateboarder, Sundee White from San Francisco was featured. There was no shying away from the challenges Sundee experienced like being told that she shouldn’t skate because she would get hurt or the more blatant message that “chicks can’t skate.” The article emphasized the importance of girls seeing each other being active at the skate park or out on the street, and Sundee’s experiences were relatable. It was written that, Sundee “really wants to encourage other girls to get into skateboarding, so if anyone out there has any questions about the technical aspects of doing a particular trick dealing with pesky people, or just getting started, she’d like to answer. This may even be the start of a regular column, if we get enough interest.”

It appears that there was interest in skateboarding, and in 1999 Saecha Clarke was featured in the online Foxy web-zine at age 22 with a photo of her skating and DJing. The article acknowledged how Saecha and her friend, Christy Jordahl would explore Huntington Beach on their skateboards in the late 1980s when they were 15 and 16, with Christy helping Saecha get sponsored by World Industries. It was implied that even though there were few girls, they could be just as good as the guys or at least respected as part of the scene.

Coming from a contemporary perspective, it’s easy to be critical of Poot! and Foxy since there was a lot of male influence, but there was still an attempt to bring girls together and value their presence. Poot! is not Rookie Skateboards and Foxy is not the Villa Villa Cola zine but there’s still a place for these initiatives in this history. Keva Marie didn’t consider Poot! to be “commercial,” at least, not on par with a big brand like Quiksilver and Roxy, but corporate values were still part of it and ultimately, the demise of Poot! was related to money, even though they were pumping out four clothing lines a year and had a massive following.

Keva Marie shared with Yeah Girl that she was let go because Poot! and her very brief shoe company, Choes “didn’t make enough money” and Foundation was adding other brands to their roster. “I just got called into the office and Tod said, ‘you’re fired. I gotta let you go.’” And that was that. Tod owned it all and Keva Marie had to clear out her office and leave. It sounded really awful and reveals the true colors of the skateboarding industry. Female-related content and products are accepted if they’re making money, but always the first to get cut if there’s any financial insecurity because the industry is predominately run by men. And that’s where change really needs to happen (thank goodness for brands like Meow skateboards run by the legendary Lisa Whitaker).

In the conclusion of the Yeah Girl article, Keva Marie recognized that the world has evolved with the expansion of gender identity, and that Poot! was very “girl power” and probably best to leave it in the past. Plus, if their goal was helping girls “be real girls” that might be triggering because there really is no one version of “authentic girlhood.” For Keva Marie, Poot! was never really about skateboarding but more about the “Girls Kick Ass” movement, and being youthful, daring and claiming space.

Reference:

- Howe, Susanna. “Players: Who’s who in action.” PAPER Guide (1995 ?).

- Huston, Sarah. “Behind the brand: Keva Marie Dine of Poot!” Yeah Girl (June 25, 2020).