Patty Segovia (Krause) was born and raised in Los Angeles and is revered for being the organizer and promoter of the All Girl Skate Jam (AGSJ) from 1997-2013, as well as a photographer. The AGSJ started out in 1990 as a girls’ vert demo at an NSA contest in Reno, Nevada, before returning with a vengeance in 1997, gaining momentum with each contest including a collaboration with the Vans Warped Tour and contests hosted in a variety of locations, including the North Shore of O‘ahu and San Sebastián, Spain.

Photo on the left was published in Equal Time zine (April 1989) and on the right, circa 1990 by Cara-beth Burnside

Patty created opportunities and awareness for both beginner and highly skilled competitive skaters during a period when the industry was convinced that female skaters were non-existent, and that women were not a viable market or worth promoting. Patty intentionally carved out space exclusively for female skateboarders when other contest organizers opted not to include a division for girls or treated them like a sideshow.

In an interview with Xavier Lannes, Patty said that she was introduced to skateboarding around age 10 after seeing skateboards being sold at a store near her house. “I asked my Dad to buy me one and he did. He soon got rid of it once I started getting scraped and bruised.” In the LA Times, Patty said her dad was afraid she’d get hurt. “I was forced to do piano, jazz, tap and ballet… I used to cry on my way to lessons” (Carpenter). Patty acknowledged that, while her mom loved watching the Dodgers, her parents were not athletic, although her dad would eventually help out at some of the AGSJ events.

Above: Patty’s cousin Tony Jetton

Even after being deprived of her skateboard (or perhaps because of it!) Patty remained fascinated with skateboarding. It helped that her cousin, a pro skater from the 1970s named Tony “Rock” Jetton who rode for Santa Cruz stayed with her family when she was 16. “I was stoked to see him do endless 360’s and was the buzz at the South Gate Sports Center where everyone used to hang out” (Lannes).

By the mid 1980s, when she was 18 years old, Patty was re-introduced to skateboarding thanks to a boyfriend, but this time she could pursue whatever she wanted, which she did. And yet, in Southern California in the 1980s, Patty witnessed some absurd examples of sexism in skateboarding. “It was so ridiculous. I couldn’t even go to a skate park without being heckled and having the guys tell me that I didn’t belong there” (Patterson).

Photo: Patty circa early 1990s at Imperial ditch

A Women’s Skateboard Association (WSA) had been gaining momentum since 1986 with the efforts of Bonnie Blouin who shared her vision of a girls’ skate club via her articles in Thrasher magazine, which was put into effect by Lora Lyons (Medlock). Lora contributed to Lauri Kuulei Wong’s zine Ladies Skateworld rallying female skaters to demand the return of separate contest divisions for girls at events like the California Amateur Skateboard League (CASL). Their efforts were sustained by Lynn Kramer who launched the zine Girls Who Grind in 1988, which became Equal Time – the masthead for the WSA. In 1989, they organized a small all-girls contest called the Labor Day Skate Jam where the participants could enjoy themselves.

Patty got involved and reached out to Frank Hawk at the National Skateboard Association (NSA) to propose a women’s vert demo at a Pro/Am contest in Reno, Nevada in 1990 at the Nevada State Fair, which had been exclusively for men.

JoAnn Gillespie (who had taken over the role as editor of Equal Time) shared that the courageous crew skating Reno included Patty, JoAnn, Rhonda Doyle, Lisa Campbell, and Cara-beth Burnside. The response by men was hit and miss, and JoAnn would later share in an interview that they were heckled by certain individuals while trying to warm-up, prompting JoAnn to hurl her skateboard at one person, barely avoiding a fist fight.

Fortunately, JoAnn recalled some positive aspects of her contest experience in the February 1991 issue of Equal Time. And, it sounds like Patty made the most of it. She came 3rd in the event. It was also fun because of the location. “I had a red CJ5 [jeep] with headers and a 360 engine with a bikini top. We drove that with all the girl skaters into town, total chaos” (Lannes).

The Reno contest was reviewed in the December 1990 issue of Thrasher, and in the six pages there was no mention of the women, the but top ten men in the streetstyle, freestyle, mini-ramp, and vert contests were all listed.

It was at the Reno event that Patty said she officially met Cara-beth Burnside. It turned out that CB grew-up just fifteen minutes away from Patty in Orange County, so there was an instant connection. Patty recalled how in 1990, the two would sit on their skateboards outside the Action Sports Retailer (ASR) “in San Diego asking people for their badges so we could get into the show” (Lannes). And they would go to the Vans “headquarters and skate their mini spine ramp and vert ramp over on Katella Avenue” (Lannes). Patty would even record her talented friend so they could do video analysis for CB to improve her tricks in both skateboarding and snowboarding.

Photos: Members of the Women’s Skateboard Network at the Powell Skate Zone, taken by Ethan Fox, director of SK8HERS published in the October 1992 issue of Thrasher. Patty is seated in the center, in a white t-shirt in between JoAnn Gillespie and Stephanie Massey.

Patty said she ended up traveling with CB becoming “skate gypsies” (Patterson), but even though she was accompanied by the most recognizable female skateboarder in the world, it made little difference when it came to their treatment by most male skaters. In fact, the snake sessions (when skaters cut each other off) at local ramps seemed to intensify when they tried to skate, as though the guys wanted to assert themselves in “their” space and reject the presence of female skaters with concerted effort.

Patty suspected that, “Guys may feel threatened by girls that skate better than them. On the other hand I must admit I’ve had special treatment at skateparks where guys let me go first. Mike McGill used to let me skate his skatepark for free in Carlsbad in the late 80’s because he knew on a Friday evening in a park packed [with] guys I would hardly get any runs on the ramps. Eddie Elguera aka El Gato would put his board out as if he was dropping in on the ramp during a snake session and would turn to me and say, ‘Go!’” (Lannes).

By 1992, Equal Time zine had a distribution of 1000 and 250 members, and that year the first women’s only skateboard video called SK8HERS (1992, Ethan Fox) was released celebrating 14 skaters. Patty had a part in the video and bantered with Cara-beth throughout. Unfortunately, no mainstream skateboard magazines celebrated their accomplishment. The video went practically ignored by the industry [see YouTube for full recording].

Meanwhile, Patty would simply not give up her vision of elevating friends like Cara-beth and all the talent that was emerging during the 1990s because she believed that they deserved sponsorship and media attention just like the guys. While the industry suggested that skaters like Jaime Reyes and Elissa Steamer were rare exceptions and not representative of what girls might accomplish with a little support, Patty knew how deep and expansive the community had become. She also knew that with more opportunities and visibility, the level of skill would rapidly progress because girls need role models, and to see other girls accomplishing new feats to believe that they are also capable. This would be no easy battle.

Patty then pursued a Sociology degree from the University of California-Santa Barbara but was still connected to the scene. In fact, Patty continued to frequent the ASR trade show to find other female skateboarders and build community, which resulted in some ground-breaking decisions.

In the book, Skate Girl: A Girl’s Guide to Skateboarding (2007) which Patty co-authored with Rebecca Heller, she wrote about her motivation. “For years, all I heard from other guys and skateboard industry people was ‘Girls can’t skate’ or ‘Girl skaters don’t deserve to be paid’… By 1996, I knew a void still existed in the girls’ skateboarding world so I created the first ever event with a prize purse for the girls” (Segovia).

Patty was age 25 when she decided to make the All Girl Skate Jam official and started sourcing sponsors. “I just thought why not get some prize money and throw in some prizes and make it a contest?” (Patterson). Patty recognized that “contests are a social event and important for society. They spread awareness and educate the mainstream” (Lannes), or in the case of women, they educate the male-dominated scene.

The reaction by men in the skateboard industry to Patty’s efforts to organize an all-girl contest was condemnation. “I had to create a revolution… Guys were like, ‘What do you think you’re doing? You can’t do this. There are not even enough girl skaters to do an all-girl skate event” (Patterson). How wrong they were! “Contestants from Canada, Brazil, Japan and Switzerland came all the way out to San Diego, California—imagine the great efforts and sacrifices these girls made just to skate” (Segovia).

The first official AGSJ was held on September 7th, 1997, at the Graffix Warehouse in National City near Chula Vista and San Diego. It was strategically lined up with the San Diego ASR. “I thought that a lot of the girl skaters would be there and would definitely have financial help from their sponsors who were at the trade show… Since I’m a photographer in the industry I was able to pull in a lot of media” (Sinkler). Plus, Patty would literally drive the streets and pull over if she saw girls skating to give them flyers.

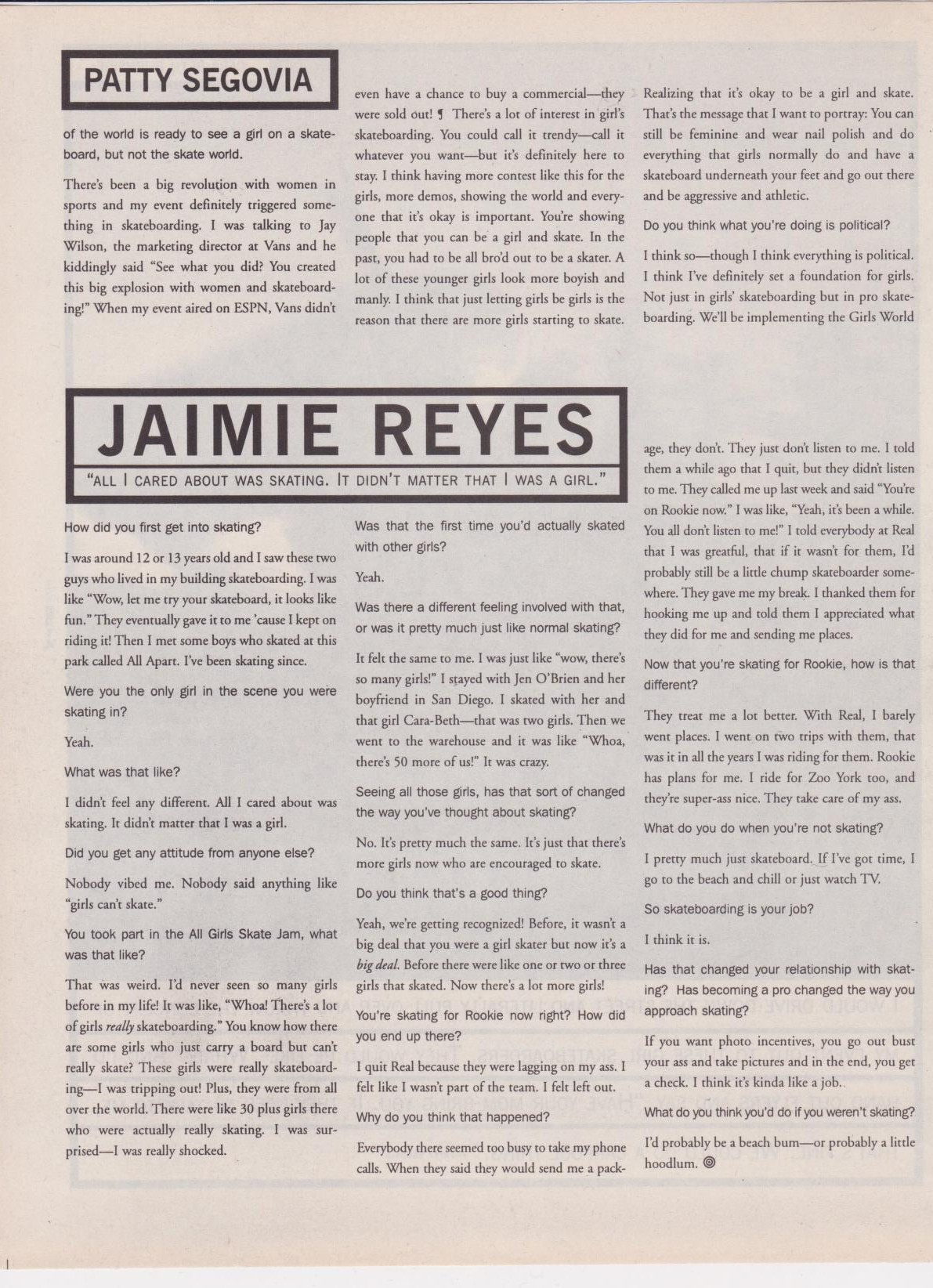

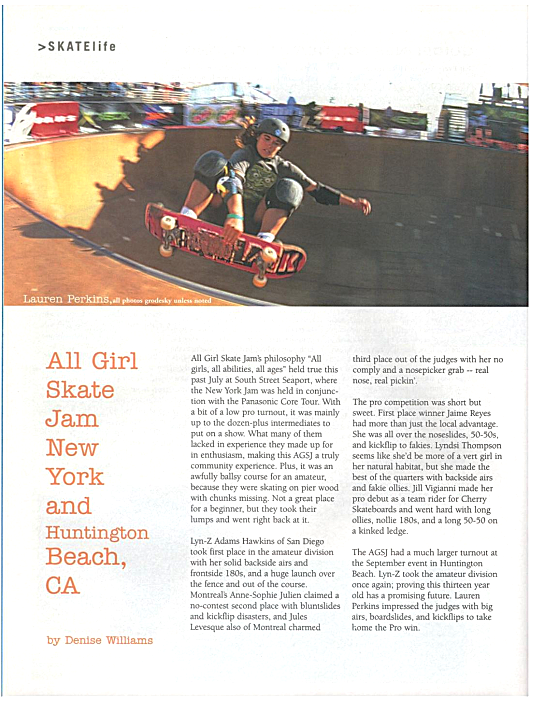

“Girls Kicking Ass” article from the February 1998 issue of TransWorld Skateboarding by Tiffany Steffens

The day arrived and the event had divisions for street and vert that drew approximately twenty-five competitors. It sounded like a super fun but crazy day. “The city turned out the power for part of the day because they happened to be working on something that day coincidentally! We were able to rent a generator and save the show to have light for the TV networks like Fox Sports Net and ESPN2 to film and air to the world” (Lannes). Patty was grateful for the help of Melissa Longfellow who was the person responsible for the ESPN connection. Melissa published the magazine Fresh and Tasty Women’s Snowboarding with Bethany Stevens out of Boston.

There was also the issue with one of the judges not showing up. Patty had some red flags since the guy initially laughed in her face when she proposed the event but agreed to be a judge when she promised him a significant fee. And then, surprise! Dude didn’t bother to show up or tell Patty. But Patty turned it into a positive and everyone at the contest cheered when she shared the backstory and how this person insisted that there were only 3 female skateboarders in existence (Sinkler).

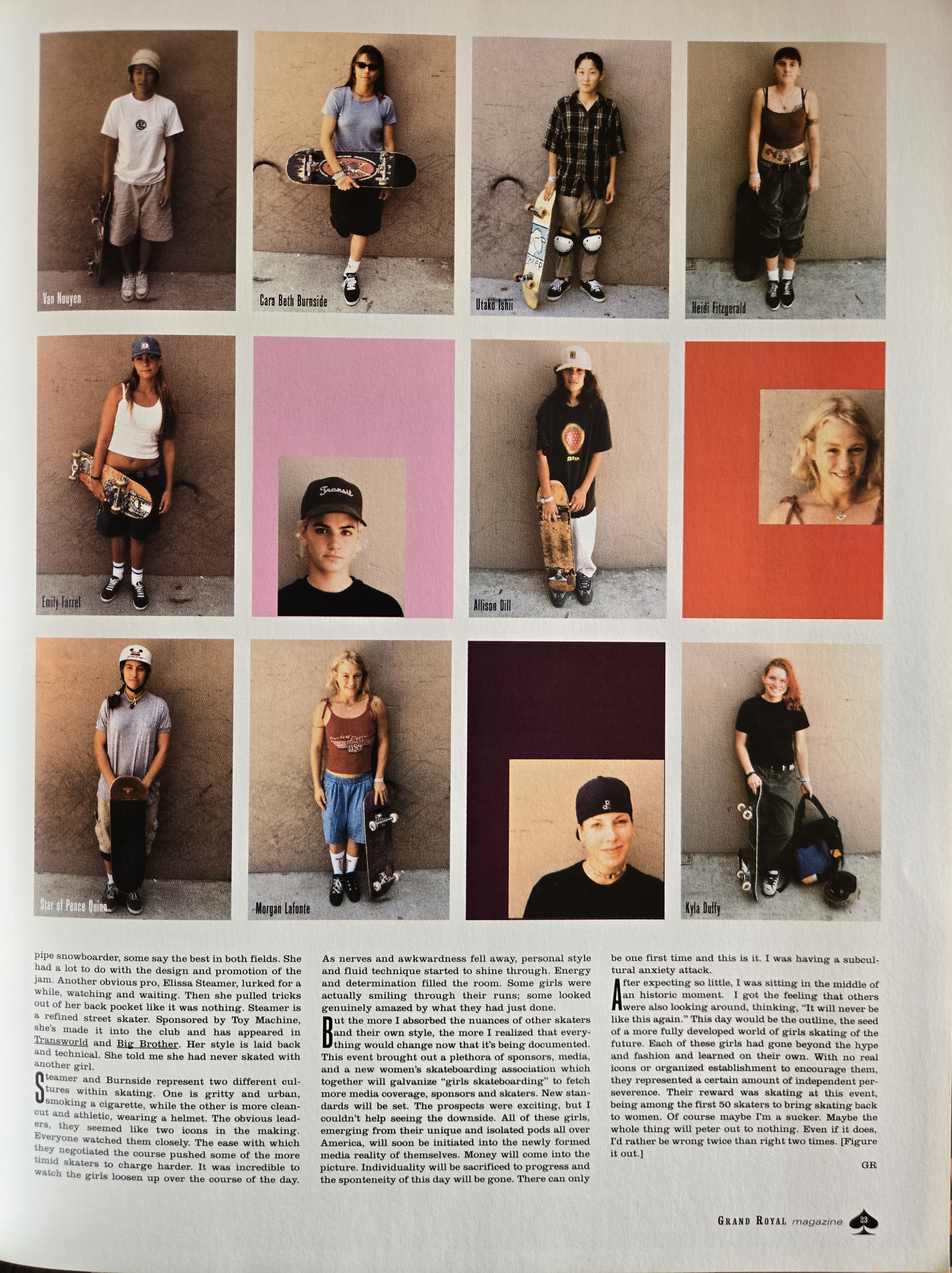

Grand Royal magazine (No. 6, 1997), which was based around the L.A. vanity record label set up in 1992 by the Beastie Boys, also stepped up! The two-page article was written by Susanna Howe and included portraits of some of the participants. The coverage completely validated Patty’s vision and gave some perspective on who these girls were.

According to the San Diego Business Journal, the companies Condé Nast Sports for Women, Harbinger Kneepads, Rookie Skateboards, TRAD WEST, and UnionBay were among her early supporters, and, of course, Vans shoes (which Patty said was the AGSJ longest running sponsor).

In the documentary, Skategirl directed by Susanne Tabata in 2006, Cara-beth, who competed at the inaugural AGSJ, said, “It was awesome, like, I had such a good time . . . Everyone there was there to see you. They weren’t there because they came to see the guys, ’cause there were no guys skating.” This was Patty’s vision: to draw attention away from the men and offer opportunity for the women to shine.

In Skategirl Patty said, “Our motto is all ages, all girls, all abilities, where you don’t have to have a sponsor. You can come and sign up the same day, show up and skate. It’s real important to try and help these girls because you don’t want them to give up. So many times Cara-Beth wanted to give up. She was frustrated but she stuck to it and that’s the difference, and Cara-Beth was a major reason why I started the All Girl Skate Jam . . . That was the start of a revolution.”

Vert skater Holly Lyons remembered her first AGSJ with enthusiasm and wrote about it on her website. She said, “[Cara-Beth Burnside] told me of an all girl’s skateboard contest in San Diego. I had to go! As far as I knew at the time, there were about five girls I knew that skated. I went to the event and was blown away. There were so many girls. I told myself I wanted to start going to every girls skate contest, so I could meet more girls like myself.” Another participant named Kyla Duffy, who was sponsored by Rookie, said the experience was amazing during an interview with Jean Zimmerman. “Everybody was so happy, and everybody felt the same way: ‘This is great, we’re doin’ it for the girls.’”

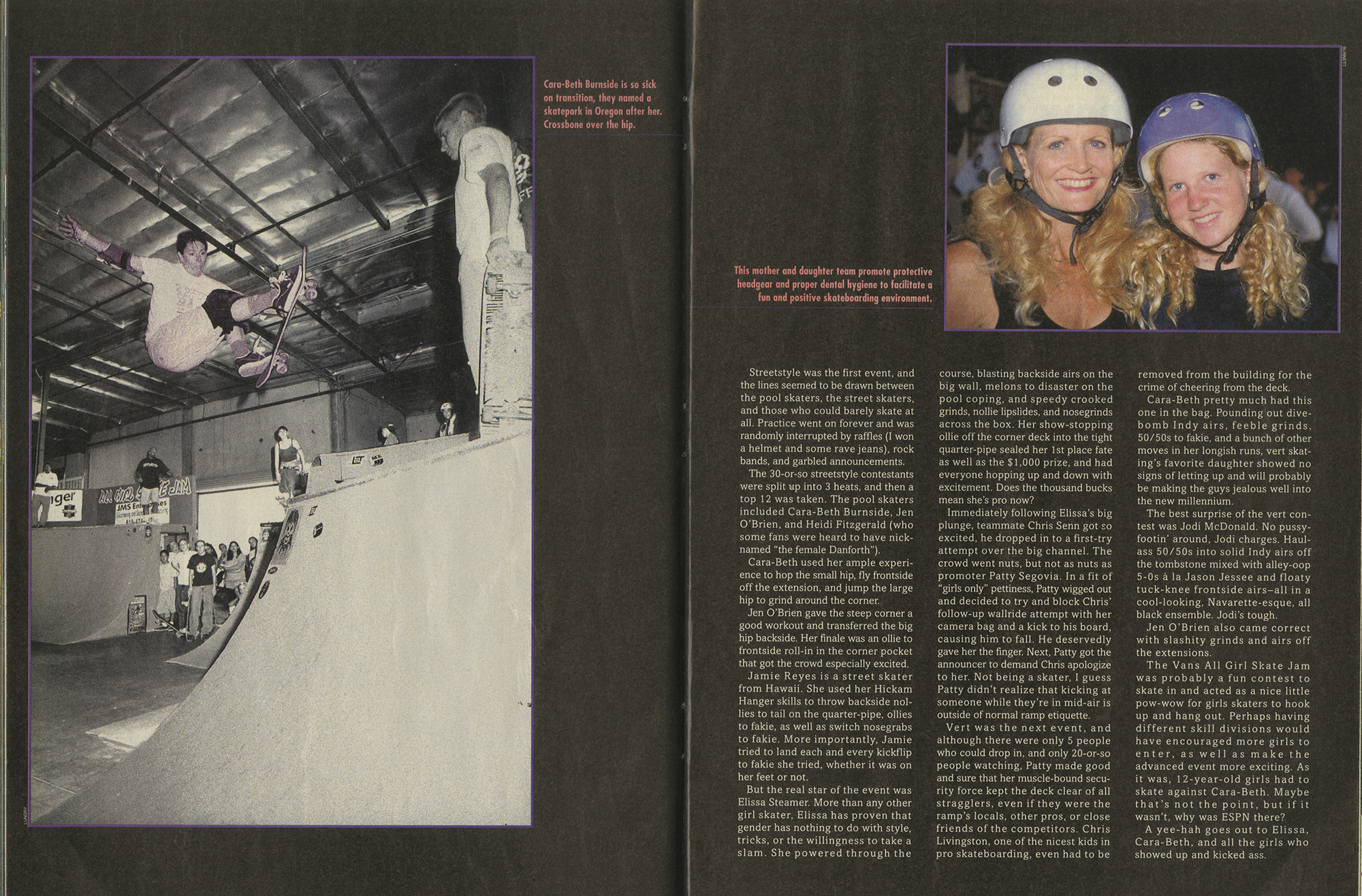

The event even attracted the attention of Thrasher magazine, with Michael Burnett writing up a four-page report for the January 1998 issue (pp 60-63) including a few stellar photos of Elissa Steamer and Cara-beth. Skaters like Jaime Reyes, Jen O’Brien, Heidi Fitzgerald, and Jodi McDonald also received props. Unfortunately, there was some confusion by a certain male pro skater about the definition of what an “All Girl” skate jam meant when he barged the course causing some tension. It reminded me of a report by Lynn Kramer in Girls Who Grind zine from the 1988 “Street Life” contest in San Diego, when the amateur men refused to get off the course to allow the girls to comfortably compete, but this time the actions were thoughtless considering what girls and women had to endure in the 80s and 90s.

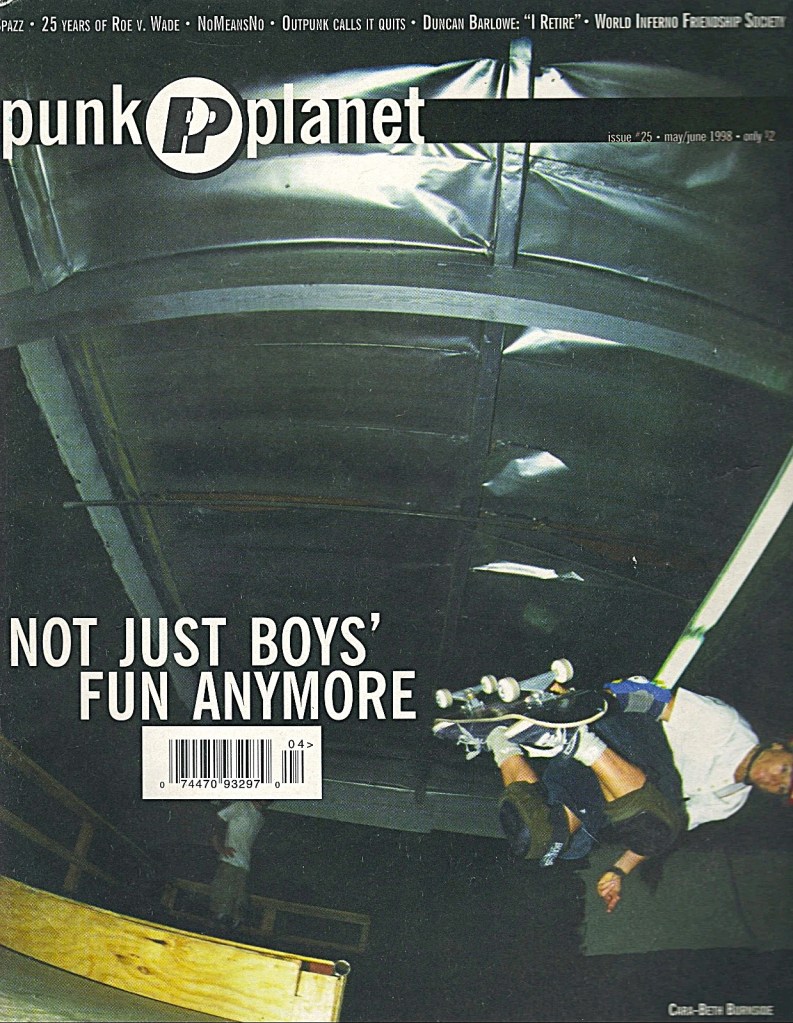

Photo: the cover of Punk Planet 25 in 1998 featuring Cara-beth Burnside, taken by Patty

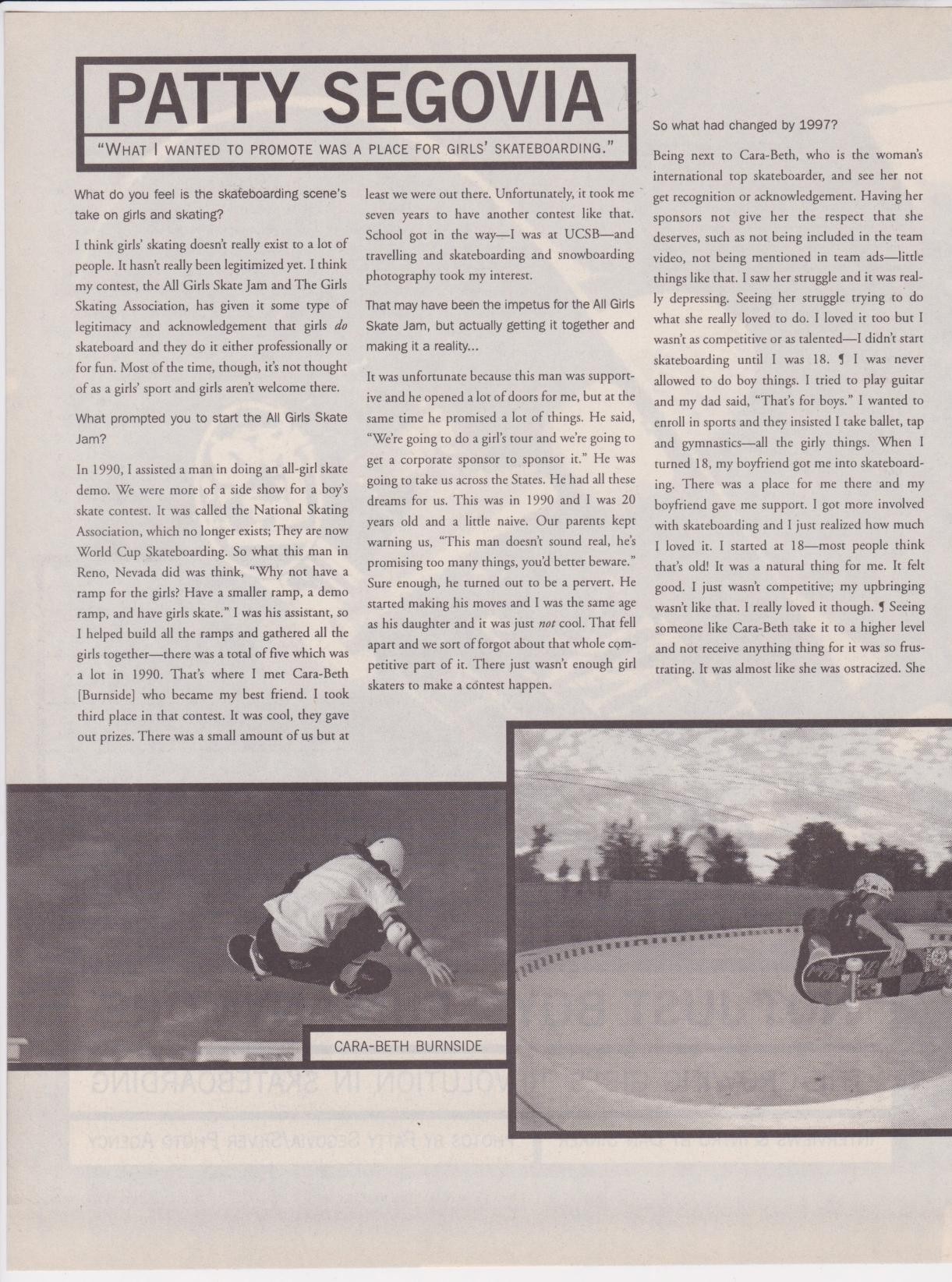

A fantastic feature called “Not Just Boys’ Fun Anymore: the growing girls revolution in skateboarding” was written in the May/June 1998 issue of Punk Planet (25) by Dan Sinkler all about the state of women’s skateboarding, with a significant interview with Patty that gave even more insight into the Reno event and how CB was ostracized. “We were invisible. We weren’t welcomed. It wasn’t an open-armed thing. It was definitely ‘You don’t belong here.’ It wasn’t a good thing. That in turn made me start taking photographs of Cara-Beth and filming her and just trying to get her out there and into the limelight to give her the acknowledgement and respect she deserved.” She also wanted the AGSJ to be an opportunity for little girls to witness CB, Jen O’Brien and Jodi McDonald “and let them come to a place and see these girls just rip and go off.”

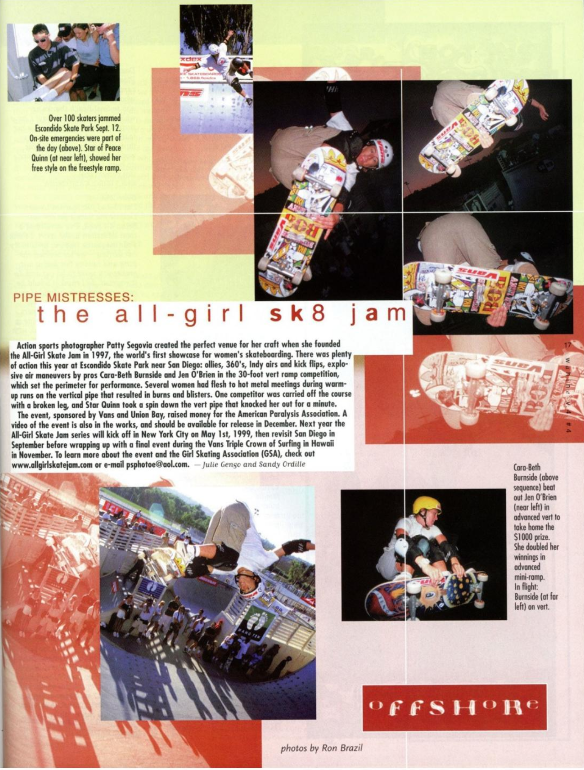

And with ESPN and Fox TV broadcasting that first event, Patty was confident that she altered people’s viewpoint on girls and skateboarding. “I think it made parents think twice. Maybe this Christmas they won’t be buying their daughter another doll – the girls might be getting a skateboard this year! That was one of my aims” (Sinkler). Someone was watching because the following year, when the event was held at Escondido, the AGSJ went from 25 to 100 competitors.

The contest was featured several times in the DIY skateboard zine Villa Villa Cola by Nicole and Tiffany Morgan since their VVC crew was based around San Diego. The pages above are from Issue 5 from 1999.

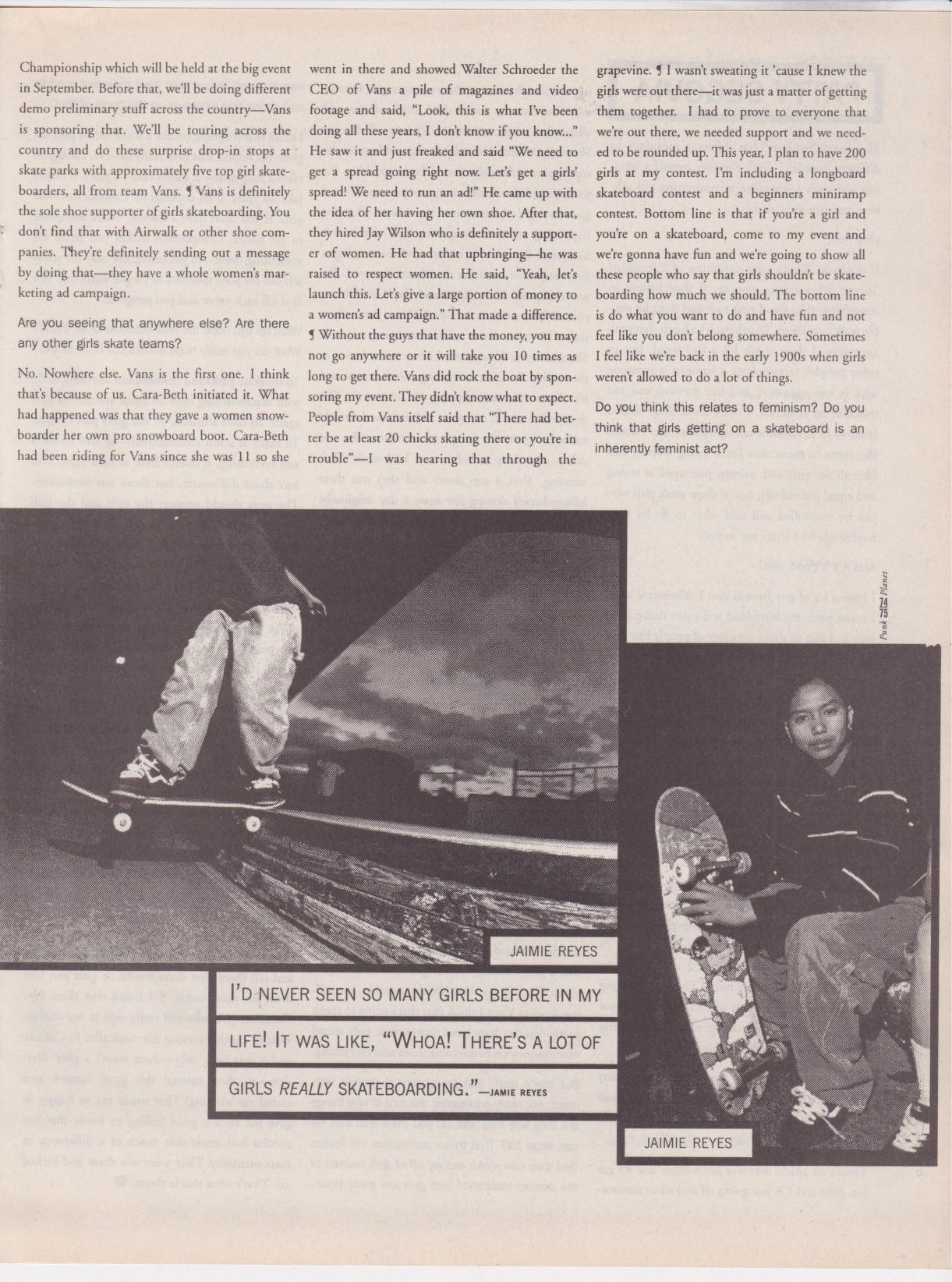

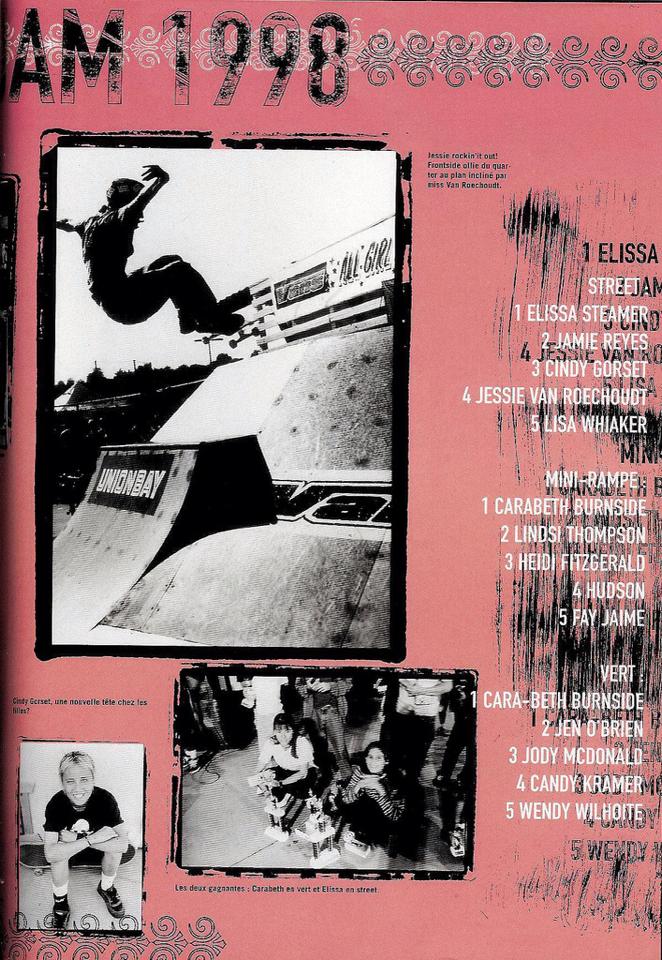

Another skateboard magazine called SUGAR from France included coverage of the event with a nice photo of the winners Cara-beth and Elissa posing with their trophies at the 1998 AGSJ, a portrait of Cindy Gorset, and an action shot of Jessie Van Roechoudt.

Wez Lundry for Thrasher magazine offered his perspective of the 1998 AGSJ in the January 1999 issue with an article called “Chicks with Sticks.” A few action photos were included of Cara-beth Burnside, Faye Jaime, Elissa Steamer, and Cindy Gorset. The report had a few cheesy elements and a few suspect quotes but overall offered some thorough coverage. The results were also included which provided a sense of the depth of competition.

Tony Hawk was interviewed at the 2000 AGSJ in San Diego for the AGSJ feature video “Level Red” by John Moore, once the contest had proven that it wasn’t a flash in the pan. Tony said, “[The women are] sort of pushed aside and not really taken seriously, and something like this, it shows that there is support for it and I think that this type of event will grow and eventually, probably it’ll make it into the X Games.”

The AGSJ continued to evolve and merged with the Vans Warped Tour hitting up over 40 cities in the summer of 2012, which was a “perfect fit” since Vans was already Patty’s main sponsor. Ironically, while Tony’s prediction came true, the X Games cancelled the women’s vert event in 2011 claiming there were not enough competitors which prompted Amelia Brodka to direct the Underexposed documentary and launch the Exposure contest, keeping Segovia’s original vision alive.

Some highlights for Patty included the growing media coverage. “I’ll never forget the call from Fox TV asking me if they could send down a crew. ESPN2 and lots of other press were present as well. Major magazines and journalists came to write about history in the making. Through this event, and via TV, magazines and international satellite feed, skater girls would be exposed to the world” (Segovia).

Newspapers and a variety of magazines also stepped up to spread the news. Covering the AGSJ was an obvious fit for magazines like Wahine, Surflife for Women, and Concrete Wave:

The Los Angeles Times wrote a piece on September 6, 1998 called “The Changing Roll of Women in Sports” by Rose Apodaca Jones. Segovia states that, “It’s no longer taboo for girls to be on a skateboard.” And when asked if a girls’ contest was contributing to gender segregation she said, “They’ve driven me to create a separate entity… It won’t be forever though. When girls catch up and get recognized, it’ll only make the sport of skateboarding better as a whole.”

The LA Times followed it up with an article a few years later on September 10, 2002 called “Skate Jam: Daring to Go Where Few Have Gone.”

When the AGSJ went overseas in July 2000 to San Sebastián, Spain, the magazine Giant Robot attempted to understand what was happening, to varying degrees of success and confusion.

Alex White and Liza Araujo of Check It Out magazine received some limelight when the Santa Cruz Sentinel published an AGSJ feature on October 16, 2001, and included their photos.

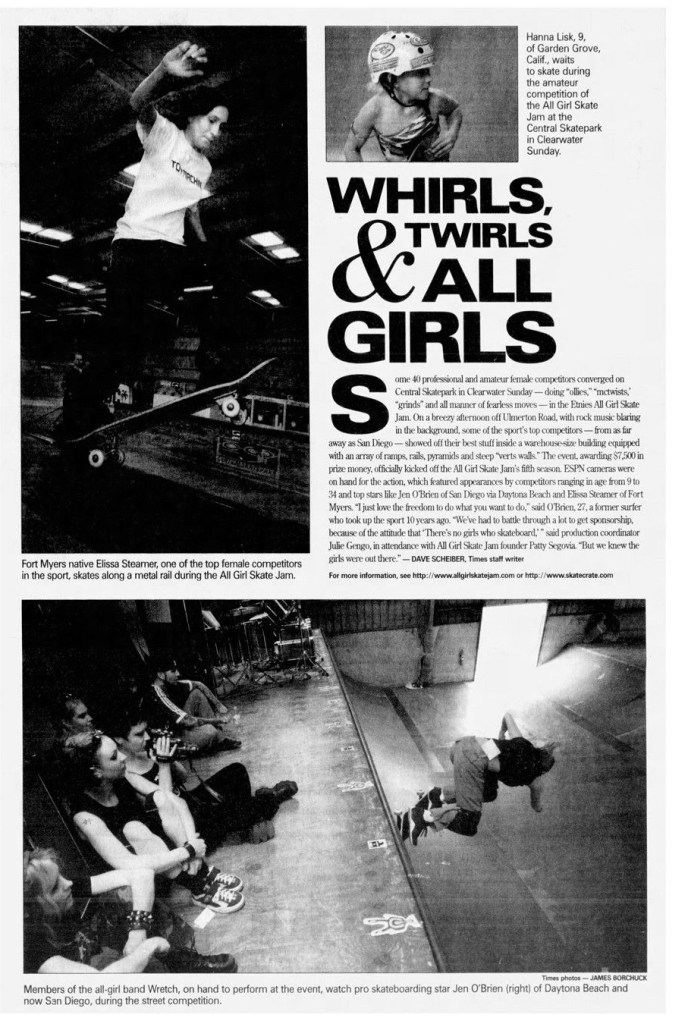

In 2001, the Tampa Bay Times reported on the AGSJ because it was hosted in Clearwater, Florida with an article called “Whirls, twirls, & Girls” by Dave Scheiber. It was noted that Etnies shoes stepped up to sponsor the event with $7500 in prize money.

The AGSJ production coordinator, Julie Gengo was quoted as saying “We’ve had to battle through a lot to get sponsorship, because of the attitude that ‘There’s no girls who skateboard’” and Segovia replied, “But we knew the girls were out there.” A shout out was given to Florida skaters Jen O’Brien of Daytona Beach and Elissa Steamer of Fort Myers, including photos (above).

The New York Times celebrated the east coast event in NYC at South Street Seaport on July 22, 2002, with Jill Viggiani featured on the front page. Patty said, “They told us the street course would be laid out on cement and they surprised us by laying it out on the pier which was narrow planks of aged wood with major gaps in between Do not ask me how but the girls skated it and made it happen. They all deserve trophies. Lyn-Z [Adams Hawkins] was only 12 years old at the time, Vanessa Torres was 11… Overall the hoops we had to jump at this event made it one of the most challenging events ever but made us stronger” (Lannes).

Juice magazine reviewed the Carlsbad contest on July 8, 2003, noting that Dickie Girls and Barbie co-sponsored the contest, alongside companies like Nikita, Tracker, and Curly Grrlz, and then everything from PETA to Kangol.

Time magazine covered AGSJ on July 26th, 2004, in an article called “The New Roll Model” explaining that there were 1.9 million women skateboarders in 2003 according to the National Sporting Goods Association (up 25% since 1999), with stats that suggested 26% of skateboarders in 2002 were female. Segovia stated that, “If girls don’t have clothing and equipment designed for them, it just adds to that sense that they don’t belong.” She also recalled how, at the launch of the AGSJ “It was like we dropped a bomb on the skating world, which was mostly male” (McLaughlin).

In the magazine SurfLife for Women (Summer 2003, p 80) there was mention of a 55 minute video celebrating the evolution of the AGSJ, and I assume this was the trailer:

Every year the hype, sponsorship, and media coverage continued. Besides Fox and ESPN2, events and news features were also aired on ABC, CNN, Discovery Health Channel, GKA Fuel TV, MTV, NBC, Nickelodeon, NPR, Planet X, and X Corps TV. The cash flow also steadily improved with $5000 and $7500 purses, which was significant for the early 2000s.

In 2007, Patty said, “The competition was originally an annual event, but the popularity and demand from women skaters is so great that the AGSJ is also involved in action and extreme sports events around the world. The AGSJ runs skate clinics for beginning skaters in 50 states as well, and offers a skate/surf camp every summer” (Segovia). These camps were established in partnership with SG Magazine, which stood for Surf, Skate, Snow Girl.

To compliment the contests, filmmaker and webmaster, Lisa Whitaker would announce the results of all divisions on her website “The Girls Skate Network” as a centralized hub since mainstream skateboarding magazines rarely bothered to track the girls’ progress, if at all. You can still see some of the early and later contest results and tons of video footage here thanks to Lisa, as well as the evolution of the AGSJ over the years. And just by looking at all the names listed of skaters who never saw any limelight you get a better sense of the growing scene.

- AGSJ San Diego 1997

- AGSJ Escondido 1998

- AGSJ Rhode Island 1999

- AGSJ San Diego 1999

- AGSJ Hawaii 1999

- AGSJ New Jersey 2000

- AGSJ San Diego 2000

- AGSJ Florida 2001

Above: an early example of what promotion on the internet looks like in 1999

Check It Out magazine, dedicated to female skateboarders thanks to Liza Araujo, Luciana Ellington, and Ana Paula Negrão of Brazil, also regularly kept track of the events and results, publishing photos and stories about their experiences.

Patty made another attempt to create a collective, this time called The International Girls’ Skateboarding Association and offered some services as a sports agent after noticing that, even though Cara-beth Burnside received a signature shoe from Vans, many other women were being shut out of sponsorship. They also had to contend with alienating photo incentive practises where companies limited the amount that women could collect. “Only pictures in certain magazines were eligible for photo incentives, and these magazines were the sort that rarely publish pictures of women, if ever” (San Diego Business Journal). The editors were always telling Patty “Sorry, there’s not enough room” whenever she submitted photos of CB (Sinkler).

Segovia established the Silver Photo Agency focusing on women in all board sports, including snowboarding and surfing. Her photos appeared in publications like Elle, Sports Illustrated for Women, Surfer Girl, Surfing Girl, Teen, and Teen People. Besides her book, Skater Girl: A Girl’s Guide to Skateboarding (2006), Patty was also sought out by publishers and released Skate Girls (Girls Rock!) the same year, and On the Edge Skateboarding in 2008, which featured Cara-beth, Lauren Perkins, and Heidi Fitzgerald.

Above: photos from SkateLife for Women magazine from 2006 featuring the AGSJ during the Vans Warped Tour

Patty’s vision upheaved the skateboard industry and forced change, such as the inclusion of contest divisions for women at major events like Slam City Jam, Globe World Cup and the X Games, although equal prize money was a whole other battle. But to get there, and to set a standard, major sacrifices were made. At one All Girl Skate Jam, Patty contributed $10,000 of her own money into the pot according to an article in the San Diego Business Journal.

Above: AGSJ board trophies from Mountain Creek 2000 and Hawaii 1999 for CB’s 1st place in vert

Patty clearly understood the importance of media, sponsorship, contests, and where skateboarding was heading. In her 2011 interview, when asked about skateboarding in the Olympics she said, “Of course it can [happen] and should. No-one thought snowboarding would ever be in the Olympics… It would be the best thing that ever happened to skateboarding.” She also felt that “if more women were heading up companies we would see more interests and know how in marketing the girls. We need women that have a vested interest in the future for girls skateboarding to have the resources and budgets to help grow the market” (Lannes).

Throughout the years, Patty continued to skate, although not everyday, and her preference was to meet up bright and early at the Vans Skatepark on a Sunday with some of her Mighty Mama skate buddies. Patty also had her share of skate injuries, like a broken wrist, fractured big toe, and cervical injury (which took 3 years to heal), but an ordeal that she learned from (Lannes). What a legend!

Photo: Xavier Lannes captured three legends at the Skateboarding Hall of Fame being Patty, alongside Peggy Oki and Patti McGee.

Above: a video still from the 2014 AGSJ “Expression Session” hosted by Holly Lyons and filmed / produced by Ethan Fox. The same director who created SK8HERS all the way back in 1992!

In conclusion, going back to the Punk Planet interview in 1998, you can see how well Patty knew the skateboard industry. She said, “I think that it’s going to take a while before girls are given the respect that they really deserve. Evolution takes a long time – it may take 10 years, it might take 20 years. It all depends on contests for these girls. If you don’t have a contest, you’re not going to get better. Competition makes you strive for something more – to get better, not only for yourself but for your sponsors or people watching. You feed off each other and you progress” (Sinkler).

Photos: A feature on Patty for Latina magazine and an announcement for a photography exhibit in August 2009 at the Ark Gallery.

The All Girl Skate Jam also became a model for female-focused contests around the world with comparable events in the late 1990s and early 2000s like the Gallaz Skate Jam (Australia, France, Germany), Wicked Wahine Bowl Series (US), Ride Like a Girl (Canada), Girls Skate Out (UK), etc.

Thank you, Patty for your passion and dedication! Skateboarding today, especially the contests and opportunities for women would not be the same (or even exist) without you and your tireless work.

Check out some of the fun All Girl Skate Jam memories and content still up on Facebook, and there’s rumour of a documentary film. Fingers crossed this happens.

References:

- Carpenter, Susan. “Move over, guys – It’s their turn to fly.” Los Angeles Times (September 10, 2002).

- Jones, Rose Apodaca. “The Changing Roll of Women in Sports.” Los Angeles Times (September 6, 1998): E4.

- Lannes, Xavier. “Interview with Patty Segovia, creator of All Girl Skate Jam.”I Skate Therefore I Am (November 2, 2011).

- Lyons, Holly. “Bio.” HollyLyons.net (2014).

- McLaughlin, Lisa. “The New Roll Model.” Time Magazine 164 No. 4(July 26, 2004).

- Moore, John. “All Girl Skate Jam – Level Red.” YouTube (November 9, 2010).

- Patterson, Tristan. “Getting Radical: skating might have been for punks, but they were as traditional as they come – until some girls came along with the toughest 180 ever.” Salon (August 28, 2000).

- Scheiber, Dave. “Whirls, twirls, & All Girls.” Tampa Bay Times (March 26, 2001).

- Segovia, Patty and Rebecca Heller. Skate Girl: A Girl’s Guide to Skateboarding (Ulysses Press, 2007).

- Sinkler, Dan. “Not Just Boys’ Fun Anymore: the growing girls’ revolution in skateboarding.” Punk Planet 25 (May/June 1998): 70-88.

- Staff Writer. “Profile – In a Jam Patty Segovia Found Success by Skating Through Life.” San Diego Business Journal (July 2, 2000).

- Tabata, Susanne (director). Skategirl (Bluebush Productions, 2006).

- Zimmerman, Jean. Raising Our Athletic Daughters: How Sports Can Build Self-Esteem and Save Girls’ Lives (Doubleday, 1998).