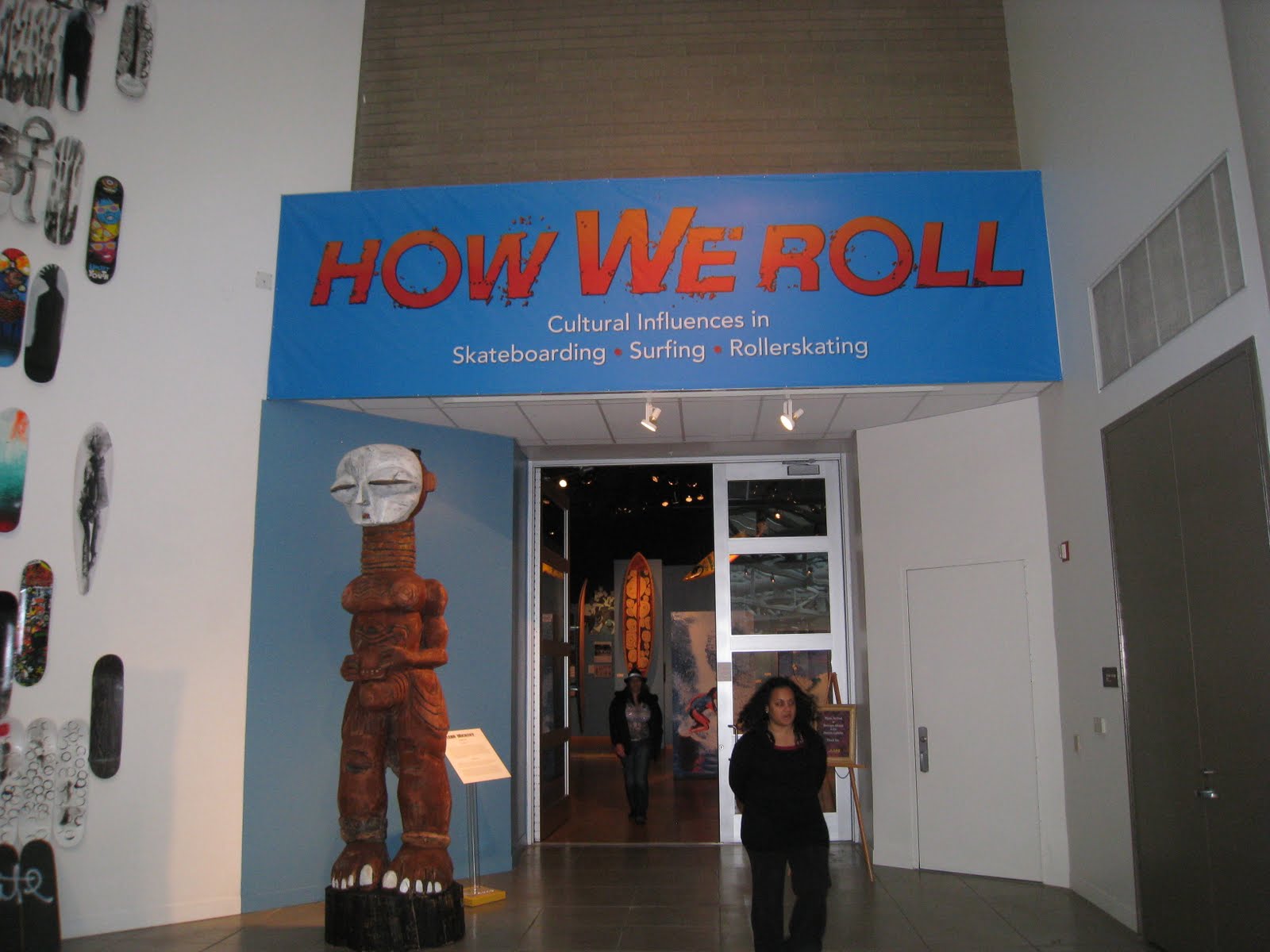

In 2010, a powerful exhibit at the California African American Museum in Los Angeles was launched called “How We Roll,” focused on Black surf and skate culture, and Ocea Lei Iverson (she/her/they/them) was part of the planning team focused on women’s participation. Ocea’s father is Black American with Indigenous heritage, and her mother is first generation Filipino, and with her long history as a skateboarder and community organizer, combined with being a resident of L.A., Ocea’s involvement was a natural fit with the exhibit, and the exhibit continues to be among the projects she is most proud of today.

I had the opportunity to interview Ocea on February 13, 2025, and learned more about her story, like the highs and lows of being “memorable” to predominately white male skateboarders as a pre-teen skater of color hitting up the local parks on a solo mission to progress in skateboarding.

Ocea shared that she was born in Santa Cruz in 1979 and grew up in Watsonville where her grandparents and mom immigrated from the Philippines and picked strawberries in the local fields for decades. Ocea said, “Maybe [skateboarding] is in my blood because my mom had one of those banana boards back in the day and would ride it going down the dirt lanes in the strawberry fields.” And then, when Ocea was around age 7, in 1987 or ‘88, a neighbor friend came over with his skateboard. Ocea had always been focused on riding BMX bikes, but she hopped on this board in the driveway of her grandparents’ place and busted out a 360 spin to the amazement of her friend who assumed she must have tried skateboarding before. “It just felt very natural, and I fell in love with it.”

Any chance she could get, Ocea would borrow this neighbor’s board and since freestyle was still popular, that’s what she practised in the paved laneway. Being a young kid, she wasn’t aware of a skateboard culture or industry, and her dad even commented that skateboarding was just a toy for kids.

A few years later, at age 11, Ocea moved with her mom to live in Minneapolis for ten years when her parents separated. Ocea acquired her own board, a Chris Miller, Santa Cruz, but at the expense of her BMX bike, which was stolen out of her gated yard. The bike had been very expensive for the time, around $500, and Ocea remembered having a blast on it, ripping around dirt jumps with her friends, but she was informed that it would not be replaced, so skateboarding was it.

Ocea then had the opportunity to skate mini-ramps thanks to an indoor skate park called “Third Lair,” which opened in 1997 on Lake Street by Mark Rodriquez, which apparently was the 3rd attempt to maintain an indoor skatepark in the location. The park was very popular as one of the largest indoors in the Midwest, and even though the park moved to Golden Valley five years later, it continued to thrive and still serves the skateboarding community today (see website).

Ocea’s mom would bring her to the park, “and it was like a bunch of white guys, pretty much between the ages of 15 and 40 in the 1990s. I see them on the vert ramp just thinking they’re like Tony Hawk.” Ocea had to laugh when, twenty years later, at a random skatepark in Indianapolis some dude approached her insisting that he knew her from Third Lair. “I told my mom that story and she’s like, well, of course he remembered you. You were like the only Black girl that he probably ever saw at the skatepark!”

With the harsh winters in Minnesota, the indoor park was a godsend for Ocea, although she did end up acquiring her very own quarter-pipe that was 6-feet high with an 8-foot extension. “Me and my friends were riding bikes, and we saw this ramp and knocked on a woman’s door and were like, ‘Hey, can we skate your ramp?’” It turned out that the ramp had been left behind by the woman’s son, who had gone to college, and she was convinced he would never skate again, so she told Ocea and her friends to take it!

“It was a big quarter-pipe and it took ten of us to push it up his huge hill and into my driveway… It just turned into a community skate place, like all the BMX bikers, rollerbladers and skaters came to my house in Golden Valley. It was a good time.” Unfortunately, Ocea’s step-dad was not exactly impressed since the quarter-pipe took up almost the whole lane but it lasted around seven years until he hauled it away and probably used it for fire wood, sometime around 1990.

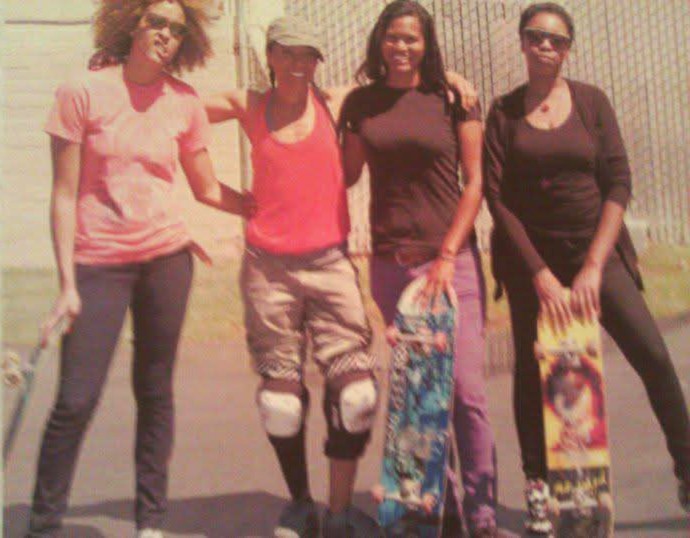

In terms of other girls to skate with in those early days, Ocea was often solo, but she remembered going to Lisa Whitaker’s website as a teenager and ordering the Villa Villa Cola video called Striking Fear Into the Hearts of Teenage Girls, which was the only video she could find online in the late 1990s. Ocea did have a poster of Cara-beth Burnside on her wall for inspiration. Although, Ocea said, “If I knew Stephanie Person existed, I would have had her poster on my wall. Somebody to look up to that actually looks like me, that I can identify with, like I’m not the only one.” Eventually, Ocea would get to meet Stephanie as part of the “How We Roll” exhibition in 2010, along with her good friends, Tierra Cobb and Erin Wade.

Photos of Ocea with Stephanie Person, Tierra Cobb and Erin Wade.

Ocea stuck with skateboarding through the 1990s and eventually found like-minded skaters when she competed in the first Wicked Wahine contest in Glendale, CA in 2004, which was a female-focused bowl and pool series organized by Tammy “Bam Bam” Tangalin-Williams and Liz Brandenberg. Ocea was making the transition west, living with family in Bakersfield before fully returning to Los Angeles in 2005, when she entered the event. The contest made a real impression on Ocea. She said, “Bam Bam’s contests were amazing – there was such support and encouragement for women coming together, and she made it very soulful and cultural, with Hawaiian chants over the bowl when it got started.” This respect for tradition and culture, along with great prizes, made it an awesome series.

Photos: Jeff Greenwood for Concrete Disciples from 2004-2012

Along with the Wicked Wahine events, Ocea competed in at least three OG Jam contests, organized by Heidi Lemmon, the Vans Combi Pool Classic, and an All Girl Skate Jam when it was offered in San Francisco at the pier as part of the Warped Tour by Patty Segovia. Throughout these events, Ocea was meeting people like Cara-Beth, Mimi Knoop, Amy Caron and Vanessa Torres, and always found it so cool that in skateboarding she could casually skate with her heroes, which is a scenario that would never happen in other pro sports, like basketball!

Image: Wicked Wahine feature in Check it Out magazine from issue #17 in 2004.

With her childhood experience hosting a quarter-pipe as a kind of community hub, Ocea understood the value of skateparks as a healthy outlet for youth. When she moved back to California, Ocea ended up collaborating with Heidi Lemmon, Bob Staton (RIP), and Jimmy Gough (Inglewood Park & Rec Manager) in hosting the Inglewood Games, in her role working for Parks and Recreation.

Ocea organized a skate team with Jimmy called Team TOOK which stood for Three One 0 Kids (310), and Staton would even give Ocea funds for gas and hotels so that she could travel with a crew of Black female skaters, part of Team Took, to attend WFSA contests in San Diego and around Orange County. Ocea regarded Heidi as a kind of skateboard mom and was inspired by her Skatepark Association of the U.S.A. (SPAUSA) that helped provide skateboard park insurance. “She even provided housing for a number of young Black skaters and also had a skate school where teens could get their diplomas.”

The Inglewood Games began in 2006 at Darby Park skatepark and was a contest that had the intention of supporting young black and brown skaters. By 2009, the contest attracted 235 entrants, making it one of the largest urban contests in the world, according to a report in the Concrete Wave (Spring 2011).

Ocea recalled how hard they had to persevere because the City kept compromising by building “skate parks” that were essentially crappy Masonite ramps in temporary settings that were supposed to serve as modular and moveable obstacles but no one found them challenging. This half-ass approach meant that the City was wasting money (approximately $600,000) instead of establishing proper skateparks, and the sites ended up becoming appealing to drug dealers rather than vibrant spaces for youth.

Regardless, the Inglewood Games was a success and Ocea managed to gather prizes and donations like skateboards, clothes, gear, and gift certificates for the kids. And, because Ocea had a connection with Barb Odanaka through the Skateboard Mama’s and Sisters of Shred network, as a fellow skateboarding mom, Ocea was given hundreds of dollars worth of Chili’s gift certificates since Barb’s husband was helping them expand the company’s diversity efforts.

Lisa Whitaker also tapped the skateboard company she was working for at the time, to throw down some quality skateboard trucks, which was greatly appreciated. “I was just so thankful. I really wish we could have continued but after three years the bureaucracy took hold and the City came in and said ‘none of these kids can skate unless they have a waiver signed.’ Well, good luck with that.”

Ocea understood the reality of the kids’ home life, especially when she was organizing the 310 Team. Tracking down parents who were working and dealing with inner city situations to sign waivers could be a real struggle, and since she wasn’t technically their guardian, Ocea couldn’t sign the forms on their behalf. The insistence of waiver forms became barriers that prevented kids from fully participating in these programs, and sometimes they felt intentional. Fortunately, the vibes towards a group of Black girls skateboarding was positive, especially in Venice, as Ocea recalled.

Ocea remembered documenting Black female skaters for the “How We Roll” exhibit along with her friend, Erin Wade to support the curator, K-Dub Williams who created Hood Games in 2005 in East Oakland. It was a real milestone for her, especially reaching out to young women in places like Brazil, but she had hoped that something more would evolve, like a blog, book, or documentary focused on forty years of Black skateboarders. With the right funding, it could still happen, but Ocea was discouraged when this aspect of skateboarding history wasn’t being automatically elevated and explored. Ocea shared the example of the Dogtown Z-boy skater Marty Grimes, who wasn’t celebrated in either the mainstream Lord of Dogtown film or Dogtown and Z-Boys documentary, even though there was plenty of footage.

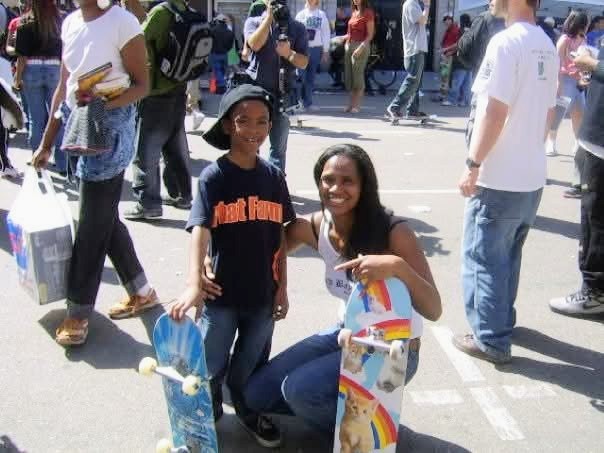

Photos: Ocea with her son in 2009 by Lisa Whitaker

Ocea spent decades helping impart anti-racist education until she read the work of Robin DiAngelo (author of White Fragility) and Tim Wise (author of The Racial Healing Handbook) and came to the understanding that it was not the onus of any person of color to explain systemic racism and that it was best left up to White Anti-racist educators like Robin and Tim.

As a two-spirit person, Ocea also understood the impact of intersectionality in skateboarding, when overlapping systems of discrimination layer up to create barriers that could often exhaust a person always processing some kind of emotional labor. Ocea recalled how, she was once approached by Michael Brooke, the editor of the Concrete Wave in connection with Black History Month. Ocea was flattered by the invitation to explore the good / the bad / the ugly, but the timing just wasn’t right for her to unpackage and critique the past and be vulnerable. And there were some challenging times, especially during the 1980s when punk was thriving.

Ocea remembered being confronted by someone who wanted to know her opinion on rap music, and then being “informed” that rap sucked and how Black people were “taking over.” She was grateful when the negative attitude towards Black culture shifted, but it was not easy being targeted. Ocea was appreciative of Black skaters like Ray Barbee, who was in a punk band, but also recognized that there was still a different power dynamic that a man could obtain versus an eleven-year-old Black girl. “A man is going to navigate spaces very differently than I do.”

Skateboarding today sometimes likes to present itself as this equitable pursuit, with white skaters who “don’t see color.” Ocea, who is a spoken word artist, even wrote a poem about this privileged phenomenon. For example, in the lead-up to Obama’s presidency, Ocea was in Orange County at the outdoor Volcom skatepark, “I was there and there was another girl, who was white. I was skating the bowl, being friendly and so she came over and dropped in to the bowl. But when she got out, I looked at her shirt and it had a picture of a monkey in association with Obama. It was a political thing, representing a Black person with a face of a monkey, my heart just kind of sank. This is supposed to be a refuge for me, and she’s just going around like it’s a normal thing to wear, like she’s not going to see a single Black person and it doesn’t matter.” Years later, Ocea noted that “I saw her again with a group of mutual friends at an industry event and I didn’t say anything to her.”

Skateboarding took its toll on Ocea, especially since wearing safety gear wasn’t always a priority. Ocea even wondered if her bursitis might have been avoided if she had heeded the advice of vert skater, Heidi Fitzgerald back in the day at a contest who said, “you better put on some pads or your knees are gonna turn to jelly!” But, what can you do! At least skateboarding helped connect Ocea with some amazing people like Heidi Lemmon, Courtney Payne-Taylor (GRO-Girls Riders Organization), Natalie Krishna Das and Jean Rusen with the AZ Las Chicas crew, Patti McGee (RIP) and her daughter, Hailey Villa, Amelia Brodka and her work with Exposure, and Micaela Ramirez through her organization Poseiden, which Ocea got involved with.

And there’s been opportunities for Ocea to meet leading Black female skaters today like Samarria Brevard, Adrianne Sloboh and Briana King, who recognize her role as a mentor at events like Ladies Day at the Berrics. And Ocea even had the opportunity skate Mary Mills’ backyard mini-ramp – another legendary Black female surfer skater!

Photos: Ocea with Mary Mills and friends!

As we wrapped up the interview, Ocea gave props to the young people who no longer wait around for permission to join “the table” in the right room or the right place where so-called decision makers operate. “They don’t care about the table. They’re not asking permission. They don’t want to be at the table, they make their own, and I wish that more OG people like myself were more like that.”

Photo: Ocea at the Berrics in 2022 with Patti McGee (RIP) and her daughter, Hailey Villa

Ocea’s vision for the future of skateboarding was that the community would come to a place of better understanding, whether one is Queer, Black, female, or non-binary, appreciating that there were people who paved the way to create change, and that there should be mutual respect for those who have overcome adversity and challenged patriarchy. “We’ve got so many systems of oppression. We’ve got racism, we’ve got colorism within this, we’ve got socio economic oppression and classism, and these layers need to be dismantled. And you can’t dismantle it if you don’t speak about it or call it out.”

You can follow Ocea on her Instagram at Ocea_Lei “Your One Black Lesbian Friend” or on Facebook at Ocea Lei. Thank you so much, Ocea for taking the time to talk with me and share some of your story!

Footage of Ocea from 2012:

And, here is a video of Ocea, competing in the Master’s division in 2013 at the Vans Combi Bowl (filmed by Lisa Whitaker and hosted on the Girls Skate Network website):