Lisa Whitaker carved out space and opportunities for girls, women and non-binary skaters at a time when they were practically non-existent. She is a skater, filmer/photographer, creative producer, webmaster, mom, and as the owner of Meow skateboards, she continues to support the community today.

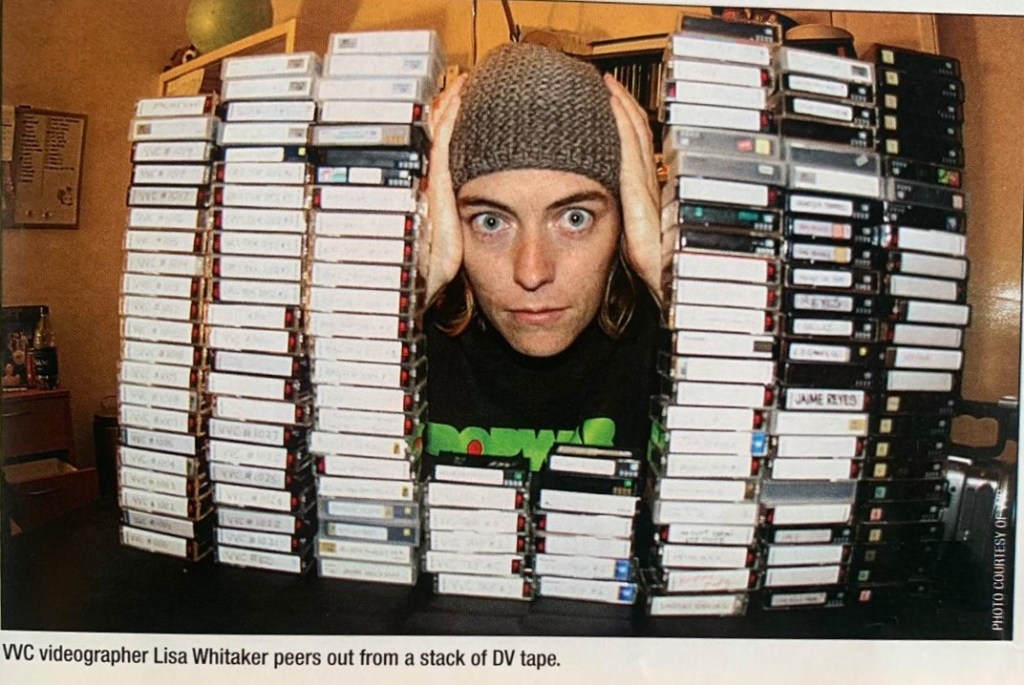

Lisa was one of very few individuals documenting women’s skateboarding in the 1990s, propelling things forward into the 2000s through web-technology and innovation. I also believe that Lisa has single-handedly acquired the most footage of female skaters ever, and that’s come down to a combination of dedication, skill, perseverance, and trust. While an acknowledgment of Lisa’s contributions is sometimes buried in the film credits, her influence is profound, and I know that I’m in a debt of gratitude for her efforts to archive the scene over the decades.

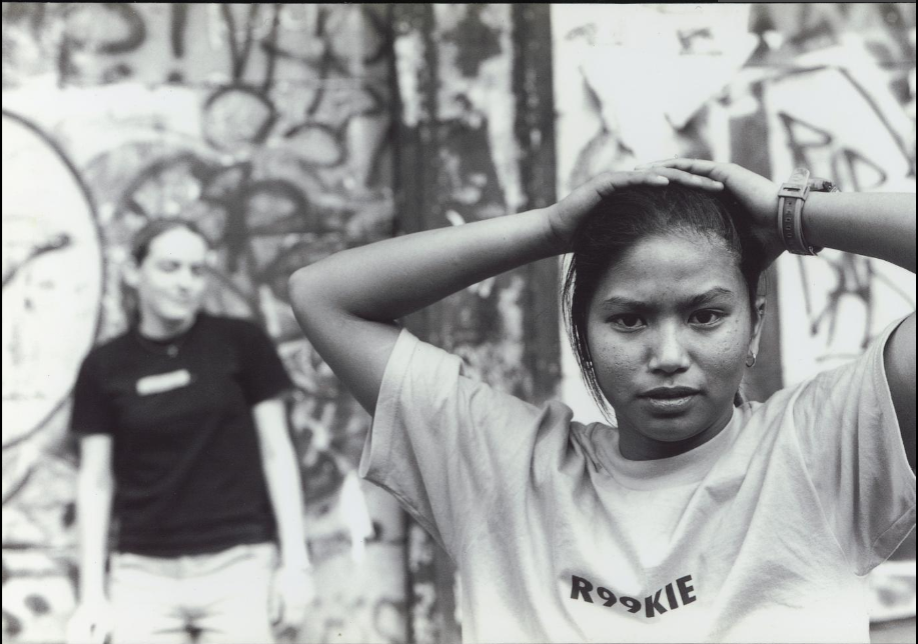

Photo: Lisa Whitaker (right) in the mid 1990s with Tiffany and Nicole Morgan of Villa Villa Cola c/o Lori Damiano

In a feature video about Meow skateboards, which Lisa launched in 2012, legendary pro skateboarder, Vanessa Torres stated, “Lisa has always just been the catalyst for women skateboarding… She’s committed and you can’t help but feed off of that… I celebrate that human daily. She’s been apart of so many pivotal moments in my life.”

As a kid growing up in Norwalk (Los Angeles county), Lisa recalled that her dad created a sketchy skateboard with old rollerskates, which resulted in her brother bailing and getting stitches in his chin on his first ride. Skateboarding was banned from their household, but fortunately it was only temporary.

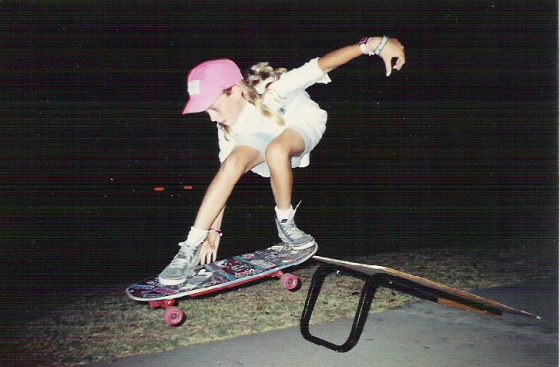

Lisa began skateboarding in 1985 at age 10, when her parents bought her a Kamikaze skateboard from a big-box store. Lisa started out skating with her best friends in the local streets. “Then sometime around 1987 one of the older kids in the neighborhood built a launch ramp. As soon as I saw it, I knew that is what I wanted to do. I talked my Dad into getting me a Powell-Peralta Lance Mountain board, discovered skate videos/magazines and learned that it was possible to do tricks” (Wang). Lisa felt that this was a turning point, and by 1988 she really began skateboarding with intention.

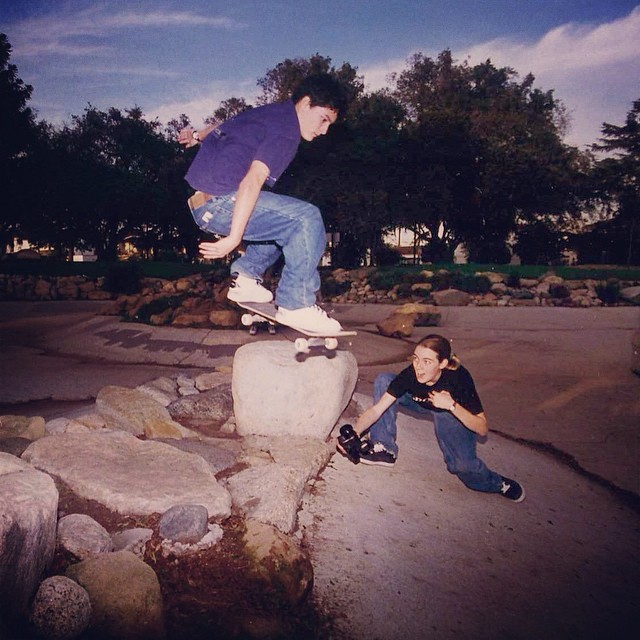

Photo: Lisa Whitaker, launch ramp 1980s

Besides skating in her neighbourhood, there was an opportunity for the kids who were sponsored or on flow for Vans to skate a mini-ramp or vert ramp in the parking-lot of the Vans factory in Orange city. Lisa would try to go with a friend every week on Wednesdays to skate transition. “Cara-beth Burnside was the one who would check everyone in and make sure you had your waiver… I didn’t know her at that point,” but it was still cool to imagine that she crossed paths with CB way back when.

By high school, Lisa started to explore the city streets, including a manual pad at her City Hall and venturing out further afield as her friends connected with other skaters. Lisa guessed that it was possibly ten years of skating before she got to experience riding a proper skatepark, because there was nothing in her vicinity growing up.

Photo: Lisa Whitaker in 1988

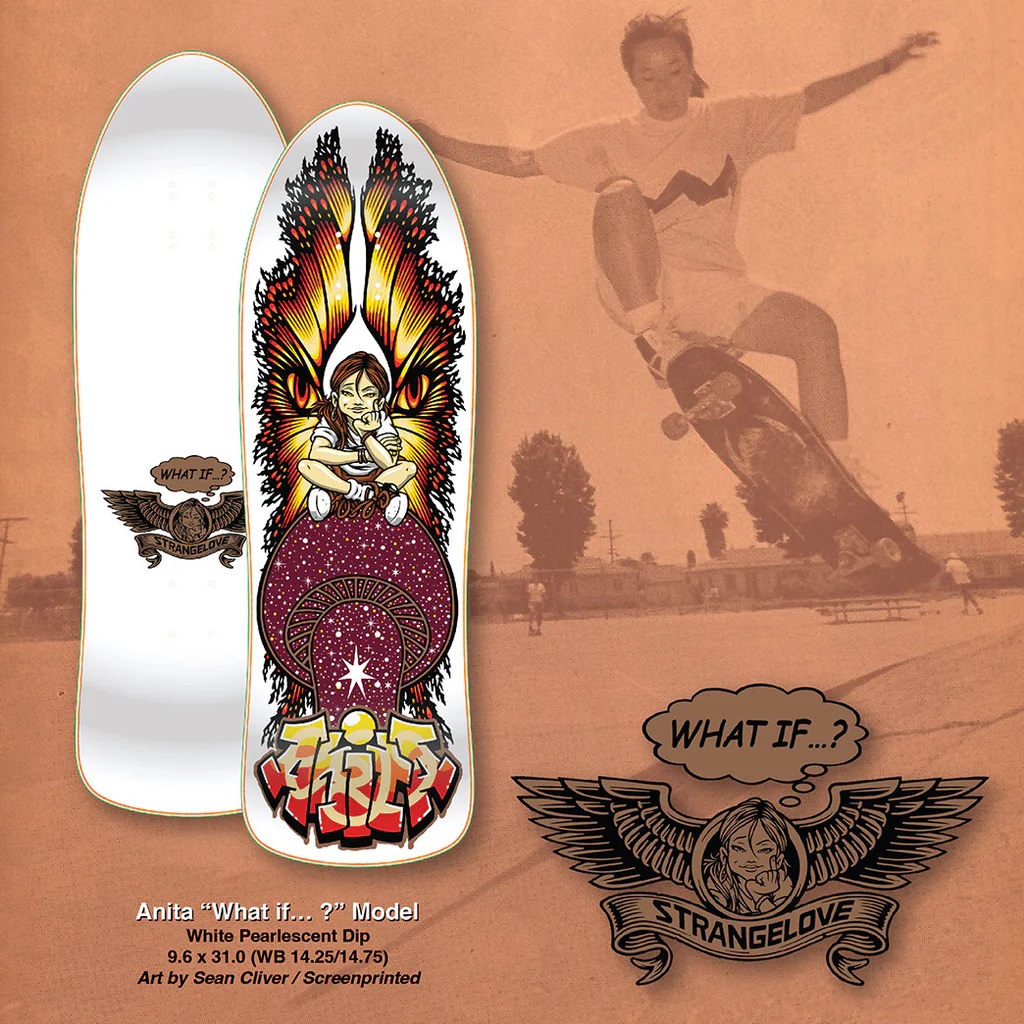

Even though Lisa’s favourite skaters were guys as a kid, “there was something way different about seeing other girls skate for some reason. Like, the little section in the Powell video [Public Domain]with Anita [Tessensohn] and Lori [Rigsbee]. That had such an impact on me” (Lima). In fact, seeing Anita Tessensohn land kickflips prompted Lisa to believe that she could do the same. Powell-Peralta included Tessensohn skating street, Sophie Bourgeois performing freestyle, and Rigsbee shredding her mini-ramp in Public Domain (1988) and in Propaganda (1990). It’s not hard to imagine that these clips were repeatedly re-wound by young women like Lisa, desperate for inspiration. Lisa even took advantage of a skateboard rental system at her local skate shop, which she would borrow for a few days and dub her own copy to study!

[Fun fact: Lisa said that when StrangeLove skateboards released Anita Tessensohn’s “What If?” signature board in 2024, she had to buy it even though she resists buying boards and has no room on her wall, but this was special!]

Lisa’s first experience filming was “a launch ramp session in front of my house with my dad’s over the shoulder VHS camcorder… about 1989” (Square). Around age 14, she began to film her friends as they improved like her buddy Anthony Acosta (the photographer), sending the footage to their sponsors, submitting content to 411 Video Magazine, among other productions and helping them with their shop videos. Lisa also created her own DIY videos including What (1990), 911 (1994) and The Wonder Years (1995). She bought her own set-up, an 8mm video camera with the money she received from graduating high school.

In her senior year of high school, likely around 1993, Lisa said that she had a connection with some skaters in Cerritos who introduced her to Van Nguyen. The two skaters had similar styles and Lisa was stoked to finally meet another girl who was as invested in skateboarding as she was.

Photo: Lisa Whitaker, one-footer from 1992 by Van Nguyen

Lisa’s network of female skaters slowly grew to include members of the Villa Villa Cola crew in San Diego. Lisa ended up being part of their early videos called Striking Fear into the Hearts of Teenage Girls (1997) in the montage section, and submitting a full part for Van:

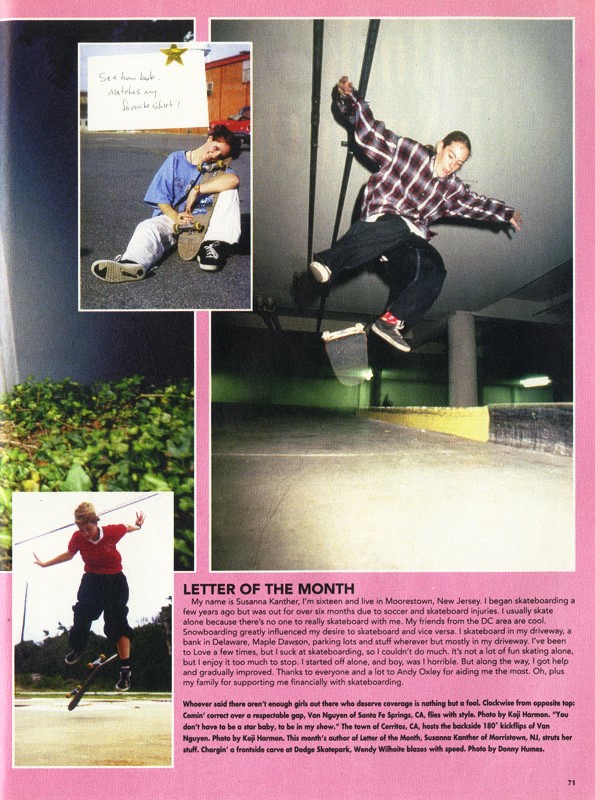

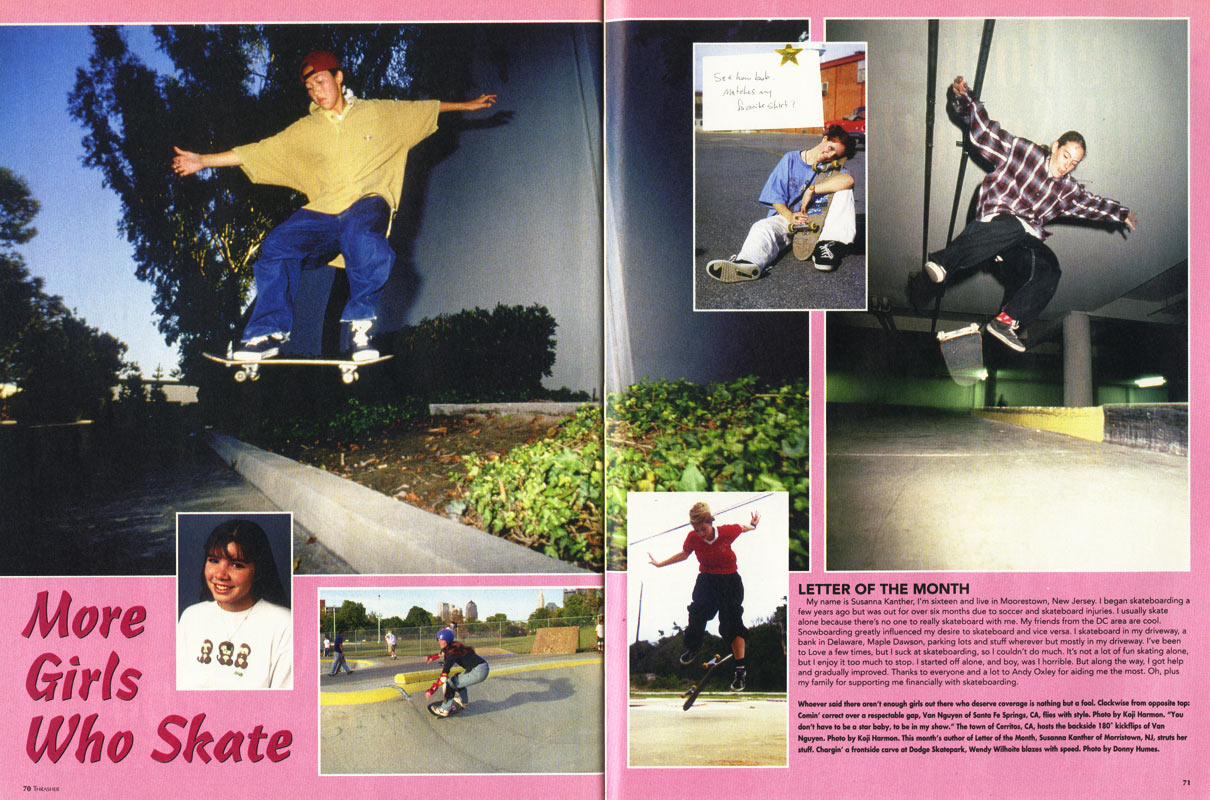

One of Lisa’s friends, Koji Harmon was a budding photographer and sent a bunch of his photos to Thrasher magazine, some of which featured Lisa. It was a surprise when the photos were published in the “Photograffiti” section in June 1994, and then a year later in a two-page collage of female skaters from March 1995 called “More Girls Who Skate.” Lisa remembered being stoked on the acknowledgment, even if her style had changed over the year, in particular her red Christmas socks!

In September 1997, we had Patty Segovia launch the first All Girl Skate Jam at the Graffix warehouse in Chula Vista, which was a game-changer! Lisa had no idea how she heard about the event, but she ended up competing in the women’s street contest, placing 7th. Lisa remembered how, on her way to the event with Van Nguyen they joked around that, “OK, what place are you going to get? First, second, or third out of the three girls that show up?” And then being surprised and delighted by the epic turn out, many of whom would become lifelong friends, like filmmaker, Monique O’Toole! Next year, in 1998 at Escondido, Lisa took 5th place in Pro Street, in 1999 she traveled to Hawaii and placed 6th, and in 2000 she tied for 8th place.

Photos: Koji Harmon documented Lisa’s street skating progression, and a great photo of her capturing the action of her friends in the 90s.

Lisa’s skateboarding abilities were getting noticed and in 1997, Catharine Lyons and Elska von Hatzfeldt (Sandor) of Rookie skateboards recruited her for their team, which was predominately female, after Lisa met Elska at the All Girl Skate Jam. Being a sponsored rider gave Lisa the opportunity to travel, compete, meet more women who were dedicated to skating and be associated with a female-owned company with a cutting-edge vision. Lisa noted that Lauren Mollica of New Jersey, who was already on Rookie, had put in a good word for her.

Photos include Rookie ads, and Lisa hanging with fellow Rookie riders, Stefanie Thomas and Jaime Reyes.

With Rookie, Lisa competed at the All Girl Skate Jams, World Cup Events, Slam City Jam, among other events. Lisa shared that, because she was over on the west coast, she was delegated to represent Rookie at the Vans Warped Tour, which toured punk bands, offered demos of “extreme sports,” and initiated a “Ladies Lounge” to celebrate female skaters and snowboarders. The organizers only had a vert ramp, so Lisa essentially hung out for a week, cruised in the tour bus with Steve Van Doren, went white water-rafting, watched bands play, and had a blast.

Going on tour with Rookie also meant traveling on an airplane for the first time (besides a short practise trip as a kid to San Fransisco), which Lisa said was so fun and mind-blowing to realize that she was taking an airplane to go skate! For example, when the crew traveled up to Vancouver, Canada for Slam City Jam, Giovanni Reda, the photographer was their “chaperone” since Catharine and Elska couldn’t go. In Skate Dreams (dir. Jessica Edwards, 2022), Lisa recalled a funny / sad situation at Slam City Jam in 2000 when she placed 4th in the women’s street, received a measly cheque for $40, which then bounced and put her in the hole!

It soon became apparent that despite the growing population of talented female riders, no one was bothering to document their progress, so Lisa stepped up and initiated change because she always had her camera with her. “I realized that a lot of these girls didn’t have any videos of themselves ‘cause there was like no outlet for it. I’d been filming these girls for like two decades basically. I knew how hungry I was for that content… I know how it felt because I was one of those girls” (Edwards). She also believed that there was no incentive for filmers to film the girls because there was no outlet for the content.

Lisa said that because she had a connection with all the skaters, “everyone was excited to get footage.” I got the impression that because Lisa had the patience to be present, to sit and wait and film the trick, that this must have been a relief for some of the girls – to have a reliable friend behind the camera, whom they trusted. The footage also needed a home and a way for female skateboarders to easily access it, and so Lisa created it.

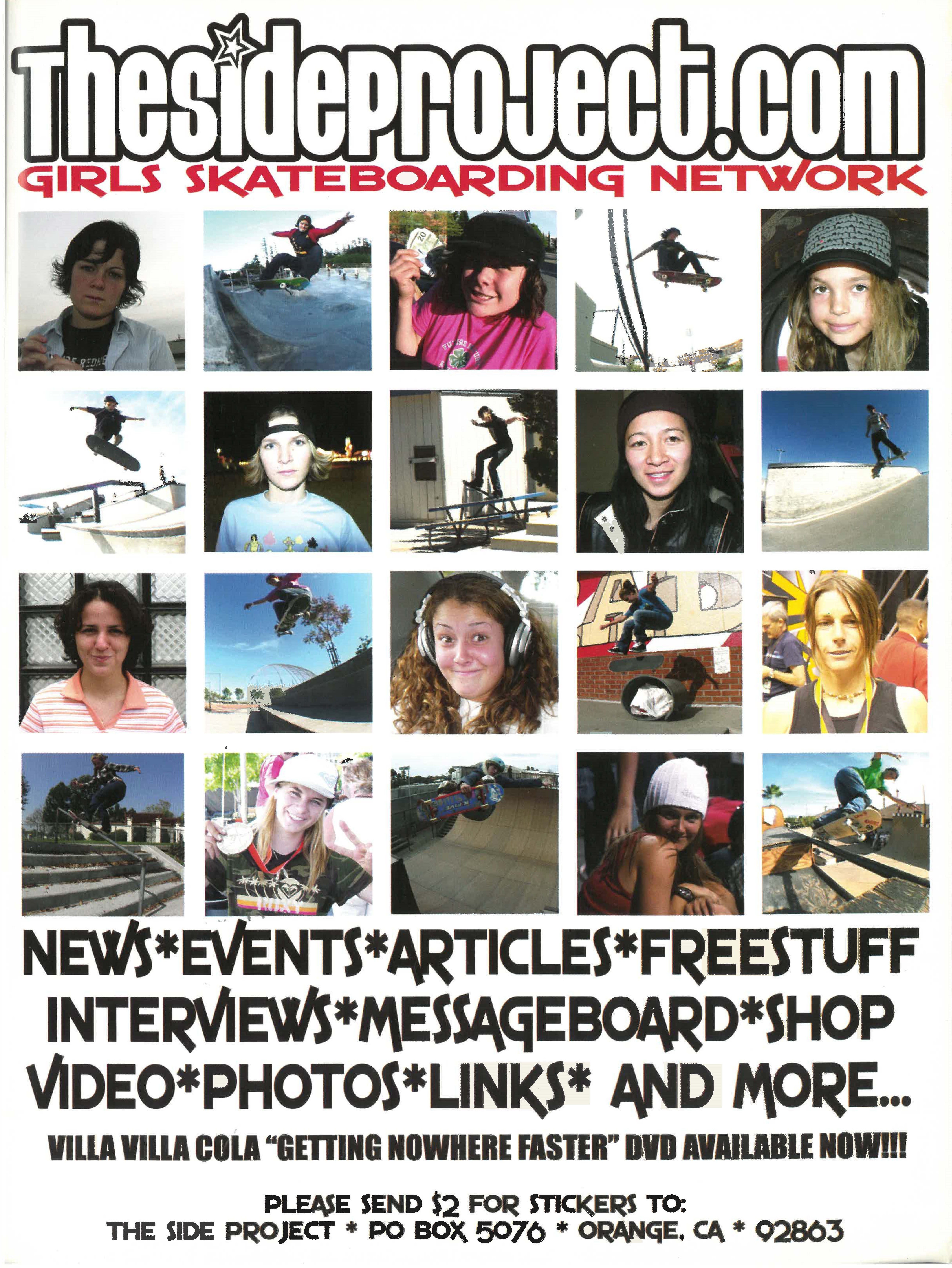

Photos: advertisements that were included in Check it Out skateboard magazine and Second Wind zine from 2004.

The internet was a new tool for communication in the late 1990s, and Lisa started out just wanting to learn the technology and decided to build a website. “The content I had was all friends and the skating I had been filming, so I used that as a demo concept to build this site, never thinking that anyone would see it, but shortly after it went up, I started receiving emails from girls around the world. Stories like, ‘I’ve always wanted to skateboard, but my parents told me it was only for boys. I found your site, showed them, they’re giving me a skateboard now,’ or they were inspired to keep skating, seeing that there was others” (Newsome).

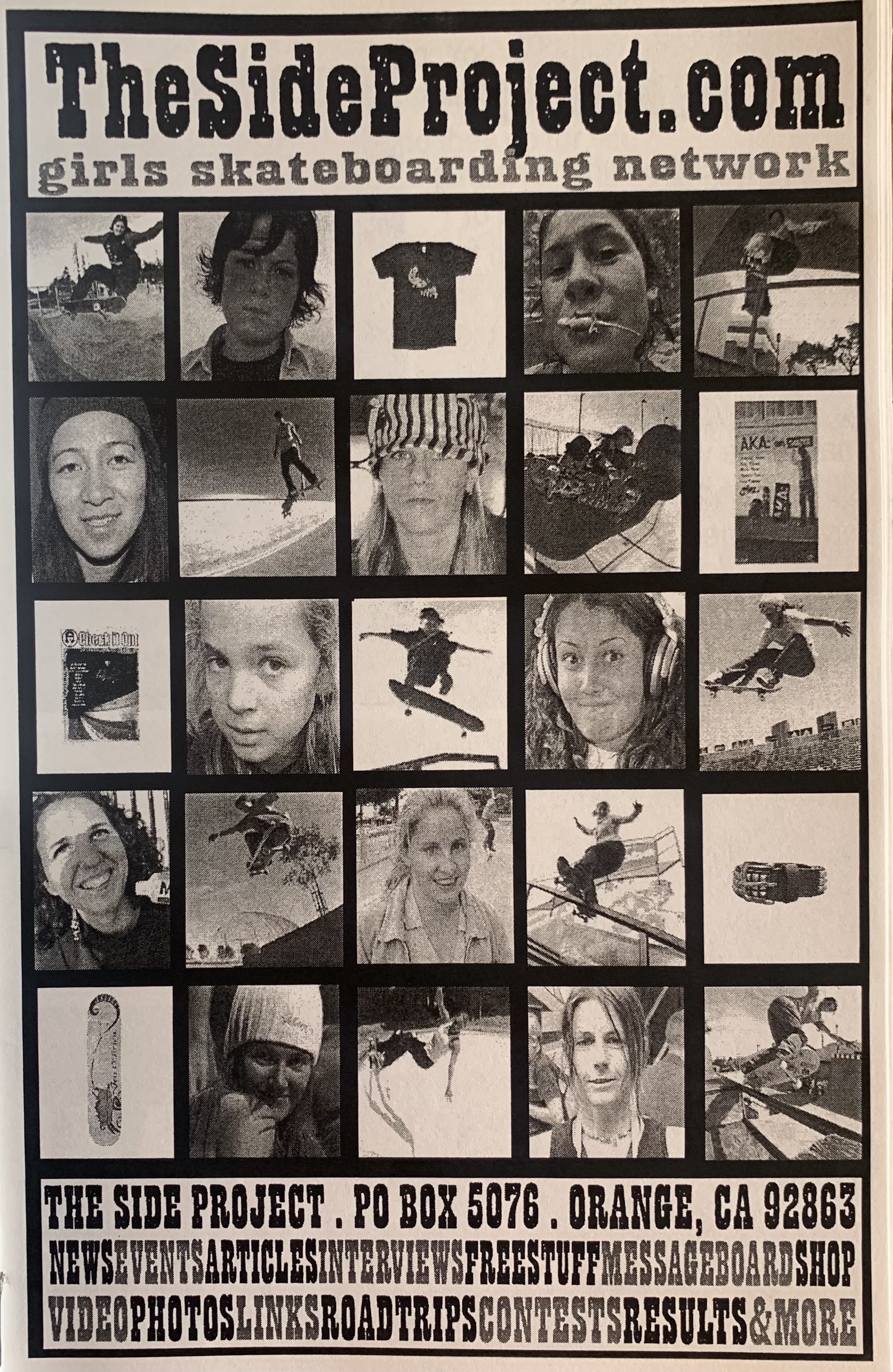

Lisa officially launched her site in 2003 and called it The Side Project, since that’s all it was intended to be, but it started to get traction and feedback. Lisa saw its potential, recognizing how important visibility was for girls, and became even more motivated, renaming the website The Girls Skate Network, which is still active!

The site was soon filled with video blogs, women’s contest results at events like the All Girl Skate Jams or Wicked Wahine series (which the mainstream magazines rarely printed), interviews, and news updates. Lisa was often on site for events like the X Games, and since the women’s event wasn’t broadcast until 2007 (and could only be seen if you watched it live), it was thanks to Lisa, recording the contest and posting it on The Side Project that female skaters around the world would get to witness the action. Finally, female skaters were getting an ounce of exposure!

Lisa’s website normalized the documentation of female skaters, provided a hub for women, and through her “Blog Cam” concept where female skaters are shown having a blast during a day-to-day skate session, the women became relatable and recognizable, garnering fans. Torres explained that in the mid-1990s, “there was no real destination for women’s skateboarding. Nobody else was filming us… Girls Skate Network was a huge focal point, a destination for any young girl or young woman to see what was going on the world of women’s skateboarding” (Newsome).

Lisa’s intention was to create a welcoming vibe, which she accomplished. Lisa did note that the comments on the YouTube channel are moderated and not immediately posted because, while she’s not opposed to criticism, there’s no need for disrespectful and hurtful remarks.

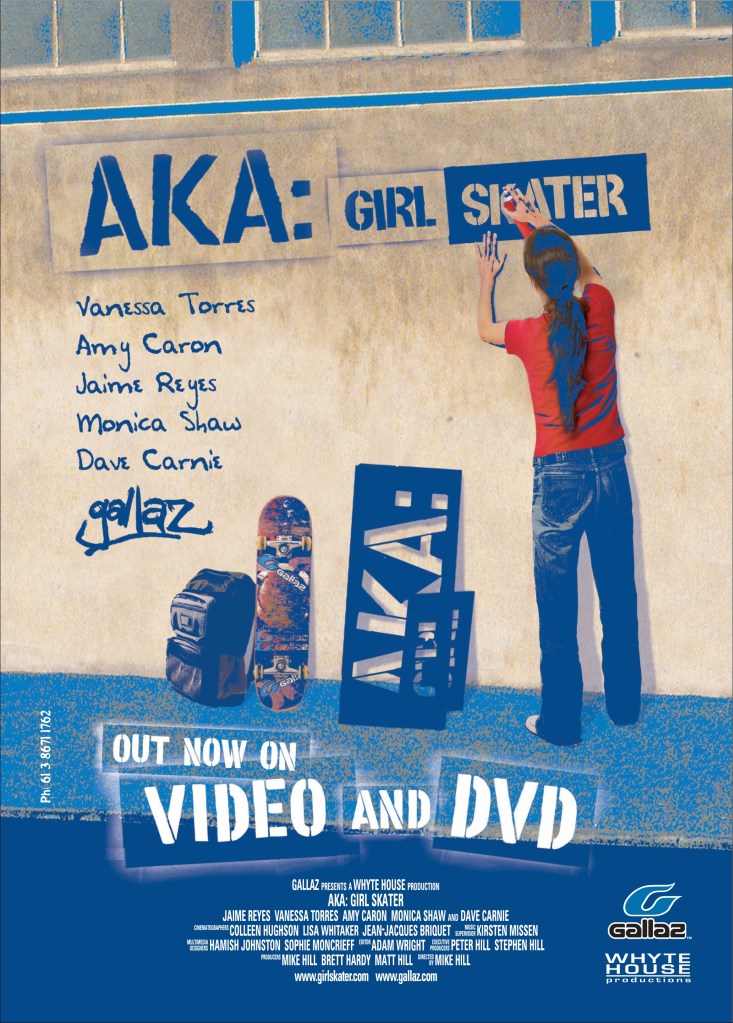

Lisa proved that women could circumnavigate the dominant media outlets that were ignoring female skaters and build a global community online. But there was hope for the mainstream industry. Globe shoes in Australia launched their female footwear brand called Gallaz in 2000, offered contests for girls alongside their Globe World Cup, and developed an incredible team of pro skaters. They even produced an epic film called AKA: Girl Skater (2003, dir. Mike Hill) with Whyte House Productions featuring the Gallaz female pro team (Jaime Reyes, Vanessa Torres, Amy Caron, Monica Shaw, Lauren Mollica, Georgina Matthews) on a tour of Australia, which Lisa contributed her footage to. She also happened to be sponsored by Gallaz at the time!

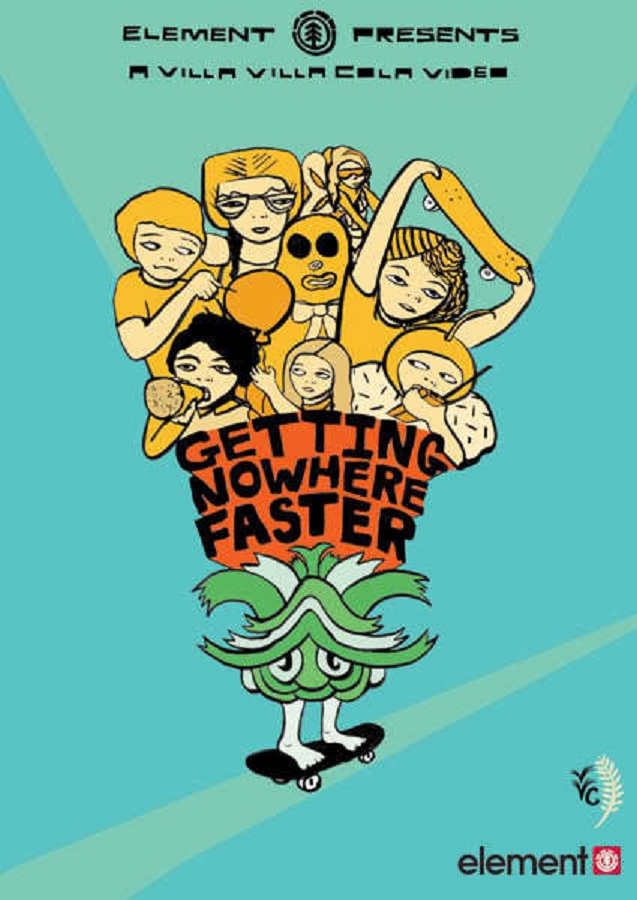

And then, thanks to Lisa’s connections with 411VM, something amazing happened! Originally, Getting Nowhere Faster, the ground-breaking skateboard video envisioned by the crew Villa Villa Cola, including Tiffany & Nicole Morgan, Lori Damiano, Faye Jamie, and Van Nguyen, was only going to be a bonus feature on an issue of 411VM. Fortunately, when Lisa dropped off the footage to Josh Friedberg, producer of 411VM, “Johnny Schillereff, the owner of Element, was there when he watched it and they were completely blown away. They had no idea that there were that many girls skating or at that level. They were like ‘forget the DVD bonus, we’ll help you make a full video’” (Lima).

Watch the entire Getting Nowhere Faster video via The Side Project YouTube channel.

In making the video, Lisa shared that the VVC crew “had worked on videos together in the past and it seemed like we all had the same views on the need for a video which will expose these girls to the rest of the world and make something they can be proud of” (Square). The film premiered in Vancouver, BC with a VVC art exhibit at Antisocial skateshop gallery, thanks to co-owner Michelle Pezel and then a film screening at the Emily Carr Art Institute Theatre on October 16, 2004.

Photo: from an article in TransWorld Business magazine (April 2005). Visit the Villa Villa Cola bio to read the whole thing.

Getting Nowhere Faster was absolutely magical, with a hilarious storyline that only VVC could concoct, and it includes a laundry list of some of the best female skaters: Alex White, Alison Matasi, Amanda Kitt, Amy Caron, Cara-beth Burnside, Connie Hartsock, Elissa Steamer, Elizabeth Nitu, Esther Godoy, Faye Jaime, Holly Lyons, Jaime Reyes, Jayme Erickson, Jen O’Brien, Jessica Krause, Jessie Van Roechoudt, Jordyn Erickson, Kea Duarte, Kenna Gallagher, Kristin Ebeling, Lauren Mollica, Lauren Perkins, Lyn-Z Adams Hawkins, Megan Black, Mimi Knoop, Monica Shaw, Patiane Freitas, Stefanie Thomas, Van Nguyen, Vanessa Torres, Violet Kimble, etc.

Lisa shared that, “My one regret now is, I was so focused on like skateboarding, skateboarding, skateboarding… I so wish that I would have documented more, kind of like the Blog cam style but back then, you don’t know at the time that 10 years from now this would be so amazing to watch.”

In 2005, pro skater Alex White created a documentary for her thesis project called Can You Kickflip? which features Lisa, among others, providing even more reflection on the state of the skateboard industry, its response to the progress of female skaters, the treatment of female competitors (ie. still hosting their events “on Sunday morning at 8am after everyone’s been partying Saturday night”), and the impact of GNF.

If you ask any female skater from the early 2000s, they will say that hands-down Getting Nowhere Faster was the most inspiring film, which helped many an isolated skater feel less alone. Lisa was then interviewed for Issue #16 of Check it Out magazine in an article called “Lisa Whitaker: Outtapocket and underpaid” by Douglass Square, and around this time, she also supported the hour-long documentary SkateGirl (2006, dir. Susanne Tabata) with her footage, which can still be enjoyed on YouTube.

In the early 2000s, Lisa became involved with “The Alliance,” which evolved into the Women’s Skateboarding Alliance during a critical time when female skaters were demanding equal contest pay and recognition for their efforts, such as having their division at the X Games televised.

Lisa became an official WSA board member alongside Cara-beth Burnside, Mimi Knoop, Alex White, Kim Woozy, and Amy Caron, among others to advocate for the skaters. It’s thanks to Lisa that this era of progress is accessible to historians online because she archived the evolution so thoroughly with her tagged blog posts on The Girls Skate Network.

Photos: Lisa Whitaker in 2008 at Visalia Camp, taken by Ana Paula Negrao

Lisa has long history working in the skateboarding industry. Not long after graduating high school she was hired to work at the first Vans skatepark because of connection with a woman in their Human Resources department. From there, she worked at a skateshop, which led to a position at Giant Skateboard distribution, then Black Label and Destructo for a decade. And during that time, Lisa gained an inside perspective of the business. She even had offers to collaborate with companies on women’s products, but it was always a guys’ vision of what was marketable for girls, and didn’t appeal to Lisa.

With her company Meow skateboards, again, it was a decision that Lisa made while recognizing that so many talented female and non-binary skaters did not have a board sponsor, when they deserved one. “I was at a major contest, and I saw that out of the top 10 girls, only one or two had a board sponsor that promoted them or included them on the team—and these were the top girls in the world. I had pro boards on my wall, but none were from any of these women. I wanted to start something where we could make boards with these girls’ names on them, something they could be a part of, to grow together” (Ramirez). Lisa knew that she was in a position to create positive opportunities for the next generation, so she went for it!

Lisa was aware that other initiatives, like Tiffany and Nicole Morgan’s attempt at a board company before Villa Villa Cola, had been rejected by skate shops, but because of the activity on her website, she knew there was a market. “So, we just started off really small. I wanted to grow it so there was a demand first… It grew organically” (Lima).

[Fun fact: Mariah Duran’s board with the cat eating pizza was the board I chose to set-up in my 40s, upon returning to skateboarding after a decade away!]

Initially, the team consisted of Vanessa Torres, Amy Caron, Kristin Ebeling, and Jen Soto, but Meow has continuously expanded, currently including Annie Guglia, Christine Cottam, Mariah Duran, Marissa Martinez, and Samarria Brevard, and skaters from abroad, Coco Yoshizawa, Liv Broder, Miriam Nelson, Nanaka Fujisawa, and Rinka Kanamori.

There’s also been big names represented by Meow over the years like Leo Baker, Poe Pinson, Savannah Headden, Shari White, Christiana Means, Nika Washington, Adrianne Sloboh, Keet Oldebeuving, Lore Bruggeman, and Liv Lovelace, although several of the skaters were just starting to get recognized when they were invited to the team. Riders on the flow team have included Julie Sandt, Kira Canales, Kristina Narayan, Tierra Cobb, and Yuri Lee.

Six years after she launched Meow, in 2018, Lisa was quoted as saying that “hopefully one day, there won’t be a need for a brand like this anymore” (Murrell), implying that she was imagining a situation in the industry where skaters, regardless of gender, would be equally supported. While that shift is definitely happening, because skateboarding is still expanding globally, Meow continues to be very relevant. In fact, Coco Yoshizawa from Japan, the 2024 gold medalist in women’s street at the 2024 Paris Olympics only had a hardware sponsor until Lisa stepped up for her through Meow before anyone even noticed her.

Did I mention that Lisa is a mom as well! Here’s an adorable photo from the Girls Skate Network (posted March 2016), which she dubbed “My Droolers.” Too cute!

In an interview with Skate Krak, Lisa also expressed gratitude to her husband, who helped initiate Meow thanks to a tax return, and now “helps pack orders when I have my hands full and he designs the catalog. Other than that I do everything myself… usually in the middle of the night when my son is sleeping.” Although, more recently, Lisa is finally operating out of a small warehouse, instead of the garage in her house!

Broadly video series, which spotlighted innovative women, produced a feature on Lisa thanks to the support of Vans shoes / Vice in July 2018 for episode 6. There’s a solid review of the Girls Skate Network website origin story, an overview of Lisa’s footage over the years, and the evolution of Meow:

SOLO skateboard magazine also stepped up in December 2018 with an interview called “Creating the Demand” by Stefan Schwinghammer. And, in 2019, Quell magazine interviewed Lisa for episode 12, which can still be enjoyed here starting around 14:20.

So, if you ride a Meow skateboard or wear their gear, you can feel confident that you’re supporting a legacy and an incredible team of skaters who are shown respect and support from Lisa. And even though we’re seeing many skateboard companies develop diverse teams, the reality is that the majority of their owners and managers are male, which means that there’s still a power imbalance within the industry and that Lisa has an important role by demonstrating that women can and should be company owners.

Photo above: Lisa showing her commitment to filming in 2008, despite the rocks!

Thank you, Lisa for all that you’ve done to build community, improve our representation in the media, and create opportunities when there were few. As Meow pro skater, Amy Caron acknowledged – “Lisa is the mayor of girls skateboarding” (Newsome).

References:

- Edwards, Jessice (dir). Skate Dreams (Film First Co, Topiary Productions, 2022).

- Lima, Maria. “Creating an archive of womxn’s skateboarding history – a conversation with Lisa Whitaker,” Skateism, June 1, 2020.

- Murrell, Andrew. “What does the rise of women in skateboarding mean for female-focused brands?” Vice.com, April 12, 2018.

- Newsome, Ted. “This is GOOD WORK: Episode 2: Lisa Whitaker and Meow Skateboards,” Red Bull Media House, September 22, 2022.

- Ramirez, Remy. “Meet the coolest all-girl skate squads in the country,” Nylon.com, May 9, 2016.

- Square, Douglass. “Lisa Whitaker: Outtapocket and underpaid,” Check it Out Skateboarding 4 Girls 16 (2004): 41-43.

- Wang, Suziie. “An interview with Lisa Whitaker,” Work in Skateboarding, March 21, 2015.

- Whitaker, Lisa. Personal interview, September 19, 2024.