Michelle Ticktin of Glasgow, Scotland was a ripping vert skater in the late 1980s and early 1990s. In October 2024, I was fortunate to connect with Michelle on Instagram, and was forwarded an update on her story by email, resulting in a major edit to this post.

When asked about what or who first inspired her to take up skateboarding, Michelle wrote,

“My brother had a mid-blue polyprop back when I was about 9 or 10, in the late 1970s. I’d skate in the house but the wooden floorboards splintered so I got a gouging more than once. Plus the skateboard was tiny with trucks that were rock solid. So all I did was go in straight lines but I loved it. About four or five years later, I got a my first full-size skateboard: a used Dogtown, a Shogo Kubo with a weird corrugated underside. I came off it street skating about a week later and it snapped in two under a car.”

Photo: Shogo Kubo’s Dogtown Airbeam sounds like a match for Michelle’s first board (c/o Sean Cliver’s blog and book Disposable).

In the November 1989 issue of the UK magazine Skateboard! an interview was published by Christian Welsh featuring Ticktin (*misspelled as “Picktin”!), which also provided some of Michelle’s history.

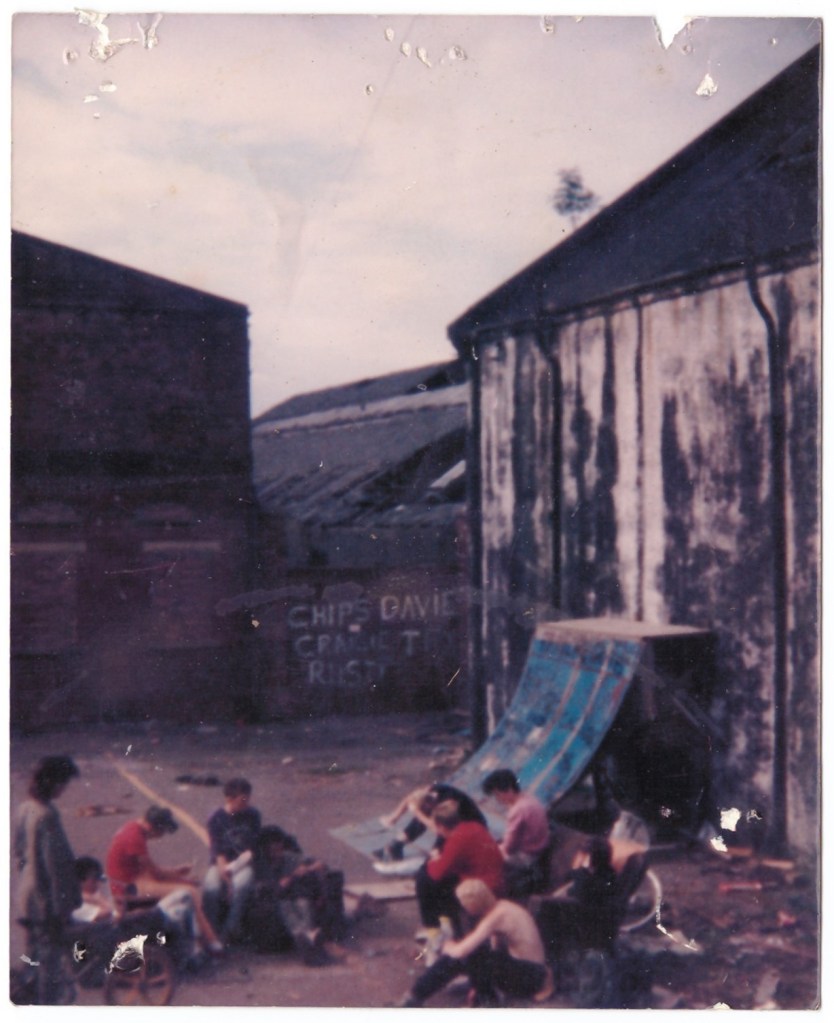

Michelle shared that upon buying a board she immediately started skating transition, since there was a local quarter-pipe and one other girl skating named Lucy, who encouraged her. In her email, Michelle explained that this quarter-pipe was built “against a disused light industrial building beside a train depot behind my mother’s tenement. I’d jump the tracks with my friends to get there. I knew Lucy from school and she hung out with a group of teenage skaters from all over who’d met, I think, at the by-then demolished Kelvingrove skatepark. Lucy was good at skating and seeing her made me want to try it again. I dropped in from the top of that quarter-pipe and broke my ankle but six weeks later when the cast came off I was at it again” (2024).

Photo: the quarter-pipe!

When I asked if her parents were supportive of her skating, Michelle wrote:

“My dad bought my first skateboards for me but beyond that I thought he didn’t care, he was just an easy going guy. But recently I found he’d kept the Skateboard! magazine I was featured in. Three decades later, I find out he was quietly proud of me. My mum didn’t pay much attention in the early years, but later she threw her hands up in despair. I took time out of education to skateboard and she thought I’d gone mad. “You can’t make a living skateboarding!” or something like that. But I was still a teenager. And, besides, some of the people I knew were getting sponsored and turning pro, setting up shops, going to the US and getting jobs in skate companies. On the other hand, she had a point: I subsequently discovered there was not much of a route to sponsorship for female vert skaters in the UK. Getting a sticker or a free T-shirt out of a UK shop or skate start-up company was hard enough. Sponsorship? Not a chance. US, European and Australian companies showed interest though, but it never happened for me. So a few years later I went back to school and my mum started breathing again” (2024).

Even when skateboarding wasn’t trendy during the early ’80s Michelle persevered, and in Skateboard! she mentioned that there was a girl named Kate who participated off and on who inspired her. Michelle skated throughout Scotland – in Glasgow, Livi (Livingston), and Brighton, where she met a girl named Teresa Williams who would arrange morning sessions on their new ramp.

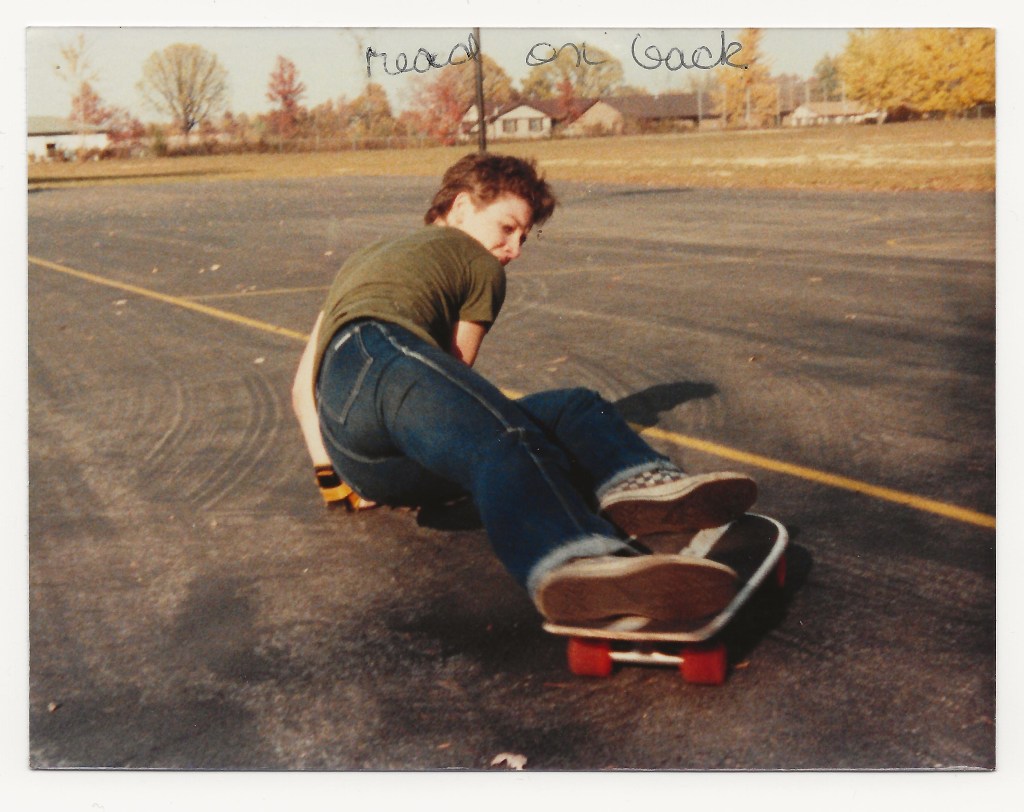

Photo: Michelle Ticktin skating street, early 1980s rocking some sweet checkered Vans. This image was found in the collection of pool skater, Cyndy Pendergast of Wisconsin, who recalled swapping photos with fellow female skaters to stay motivated.

Besides her friend Teresa, Michelle said that, “I’d seen Sue Hazel skate at a Southsea comp. As I remember it, the Southsea competitions (in the late 1980s) were really packed with contestants and drew big crowds. I personally couldn’t handle being seen, didn’t have much competition experience and I tended to perform badly in front of what was basically a 90% male audience. But Sue Hazel took the pressure just fine and always skated really well” (2024).

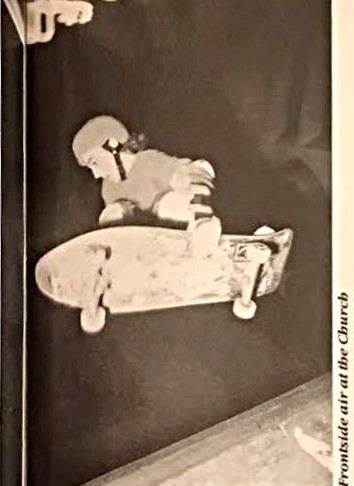

Photos: Paul Duffy, Fred MacMillan

In her interview for Skateboard!, Welsh was persistent with his questioning about Michelle’s perspective on being a female skater, and she shared it was only noticeable at competitions. Michelle wasn’t concerned about competing against the guys and said, “when you’re there and you’re skating with these people that are so good, you just want to push yourself.” The challenge was that “there’s all these men walking about and everyone’s thinking, ‘My God there’s a girl that skates!’ If there were more it wouldn’t be like that.’ And when asked if there actually were more girls out there, Michelle replied, “Oh yeah, lots. They’re everywhere. My friends are getting into it.”

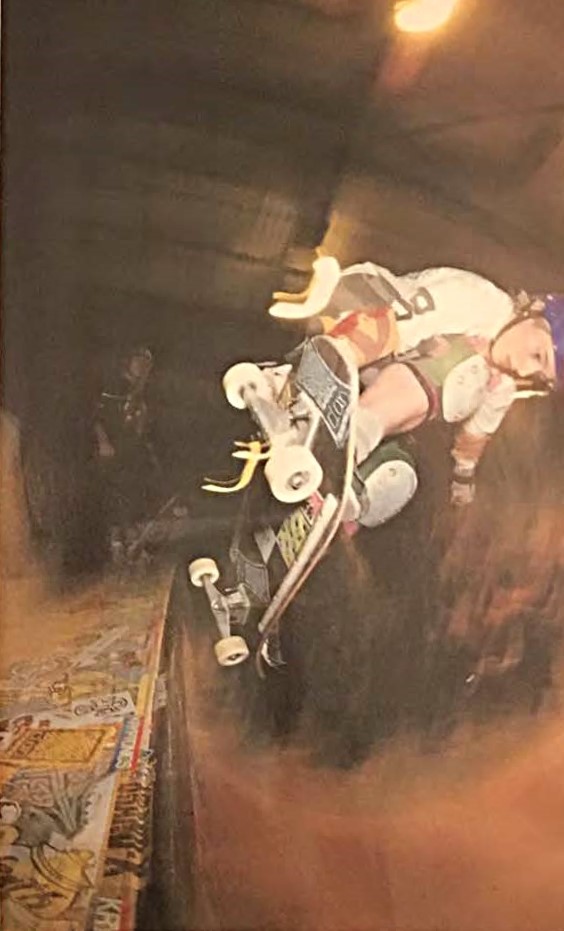

Michelle’s favourite place to skate was at “The Church” in Glasgow, officially known as Angel Lights Planetary Skatepark located in Anniesland, which she described as an oasis compared to some of her experiences elsewhere. “Looking back, The Church was a high point in my vert riding life, no doubt” (2024). The vert ramp was a skater’s mecca, and many contests were held there although the scene would later be described as cult-like due to the influence and manipulation of a charismatic leader who launched the park in 1989. Here’s a clip from BBC of the Scottish skate scene in 1988:

Michelle offered some backstory:

“People in Glasgow who I knew had set up a skatepark in a defunct church, called ‘Angel Lights Planetary Skatepark’. They called it that, I was told, to keep it positive and distance it from the skulls-and-skeletons, hyper-macho, skate-and-destroy vibe prevalent in the skate subculture at the time. I’d already visited the skatepark during a stop-off on a trip from Brighton to an Aberdeen competition: Teresa, me and two or three other Brighton skaters sessioned it all day and kipped on the mini-ramp overnight and had a hilarious time of it. That was before I’d even moved there. The Scottish skate scene was laid back, skaters were chilled; the ultra-masculinised skate vibe wasn’t a feature. I skated with people who I’d known for a long time, whose skating inspired me, and in the city I’d grown up in. I missed some bits of the Brighton skate scene, especially Teresa, but I wasn’t going back there any time soon. And, like Brighton, Glasgow was added to US pro-tour itineraries: all sorts of names-in-lights dropped by to session there. It was good times.

The people who set up Angel Lights were people I’d gone to school with and known as a teenager. Some of them held beliefs that I didn’t necessarily agree with but I liked them and it was amicable between us. And they’d done this amazing thing, which was set up a skatepark in a church. It was a huge achievement getting the premises and the financing, designing and building the ramps, organising competitions, one of which was at the city’s main indoor arena in 1988. That drew a lot of international skaters and was featured on national TV” (2024).

As far as her own experiences, Michelle progressed quickly on vert, noting that it gave her an adrenaline rush, and she would only occasionally skate street after experiencing vert. Michelle also got to meet Stephanie Person, the first black female professional skater and was pretty stoked to connect during her visit to Brighton. “Stephanie Person showed up during a European tour. She was exceptional in so many ways – super friendly, a female pro from the male-dominated US skate scene, a great skater, and a woman of colour. She was amazing!” (2024).

Photo: Livingston skatepark in 1982 taken by Chris Eggers. See the story on Dee Urquhart, the skateboarding wife of architect, Iain Urquhart who designed the Livi skatepark and initiated the Scottish Skateboard Association!

Michelle wrote, “I started skating in Glasgow and a little bit at Livingston Skatepark and that was all good teenage fun. But it wasn’t really until I went to Brighton to study that I started skating vert – at The Level, a halfpipe in the middle of the city. I loved sessioning that ramp. I learned backside, frontside and indy airs, nose picks, rock fakies, grinds, handplants, ollie airs and on and on. Skate sessions were inclusive, and me and Teresa, my skate buddy, were encouraged by all the guys. Lots of American pros were getting travel money at that time and put Brighton on their tour schedules. It was a great skate scene until it wasn’t.

I remember going into a local skate shop one day where they had a photo wall. There was one of me skating up there and someone had scrawled on it, ‘The man’s thing’ with an arrow pointing directly at me. I never found out who wrote it, no one owned up to it. Beyond it being an insult, I still don’t really understand it. And the people behind the counter left it up there for all to see. They weren’t great at customer service in that shop. I don’t think I ever went in there again. Then a moody skater having a bad day threatened me at the skatepark: ‘If I see you again, I’m going to kill you.’ It was a low point. I went back to Glasgow after that. That was around 1988-89. I was still a teenager,” (2024).

Photo: unknown in front of the Angel Lights skatepark church

With these kinds of interactions going on, Michelle couldn’t imagine the existence of a girls-only competitive series back in 1989, even when it was noted in Skateboard! that women’s surfing was successful as its own division. And yet, she was excited to be part of the Women’s Skateboarding Association which originated with Lynn Kramer, along with Sue Hazel and a friend named Kay. “I guess if there’s a recognised body of females who skate other females might not feel like such a freak when they get on a skateboard” (1989).

For contests, Michelle entered Southsea, which she hated, and Aberdeen, which she enjoyed since it was more like a jam session and she liked just having a laugh. Michelle concluded that, “I think I’m really lucky that I do skate because I do like it so much and it’s just something I really want to do. Not a lot of people find things that they really want to do. I’m so stoked that I skate” (1989).

From there, Michelle decided to travel to California with another female skater and met lots of interesting people.

“I met people at skate companies who were keen for women to join their teams. One envisaged setting up an all-women’s team and wanted me to get involved. It didn’t happen in the end, but it was nice to be considered. Of the pro riders I passed by in 1990, most were indifferent to me but some were helpful and generous towards me. That’s how I wound up on that tour with the Foundation junior crew. We drove from California via Arizona, Texas and Florida too, I think, South Carolina in a small camper van with broken air conditioning in high summer – it was boiling hot. Touring with a bunch of overheated teenage boys was ridiculous: limitless energy, loud mouthed, all farts and getting their puds out. They gave everyone shit: nicknamed me Large Marge, tore holes in my appearance, that kind of thing. It was relentless.

Eventually the guy in charge dealt with them like toddlers: giving them time-outs to get them to calm down. That tour was a coast-to-coast, comp-to-comp, skatepark-to-skatepark affair, staying in cheap motels: high points were Jeff Phillips Skatepark in Texas, after a stop-off in Phoenix, Arizona. Cara-beth Burnside and, I think, Stephanie Person, were at that Phoenix comp. The organisers wouldn’t let me compete and they weren’t nice about it. They didn’t see me as a young female vert-rider from overseas, just a potential insurance risk so they got rid of me. I made an effort to resist, but the older guy who eventually climbed the ladder to the platform and insisted I get off seemed formidable. I was later told Mr Formidable was Frank Hawk, which is plausible but unverifiable now. After that tour finished, I was back in SoCal and a pro skater took me along with him to an eye-poppingly surreal skate jam in a suburb. It was in a backyard compound with a big vert ramp and two or three mini-ramps. When I arrived a bible session was in full swing on a mini ramp flat bottom with a group of teenage boys giving it their full attention. Bible quotes were written all up the sides of the big ramp and under the ladder to the platform. I didn’t even skate that day. I left the US pretty sharpish after that and got back into education” (2024).

In an interview for a newspaper called the Brighton Argus in 1994, Michelle shared more about her trip to the United States and the professional skateboarding scene. “It was a revelation to see these guys actually running businesses, making a living out of skateboarding and they were only in their mid-20s” (1994). Michelle recalled how impressed she was with the booming commercial activity she witnessed, like going to a World Industries warehouse in 1990 just stacked with inventory and the impact of ambient advertising through marketing vehicles like skateboard stickers. But she understood that, “skateboarding wasn’t a homogeneous subculture back then, far from it, misogyny – some of it militant – was widespread in the skate scene (just as in the rest of society). In 1989, the UK’s Skateboard! magazine, re-quoted from a TransWorld magazine article in which two prominent SoCal-based pro skaters had voiced their attitudes to women’s skateboarding, one expressing his opposition, the other indifference. It was also at about that time that I started seeing ads in US-based skate magazines that obviously took their aesthetic cues from porn. That aesthetic eventually became even more explicit in packaging and advertising, e.g. board graphics” (2024).

Michelle was wary of the impact of a male-dominated industry and commented on the violence in the scene, which came to a head when Mark Anthony “Gator” Rogowski was convicted of raping and murdering Jessica Bergsten in 1991. “Most of the men had warped ways of thinking and there was so much casual violence around” (1994). Michelle remembered meeting a super-friendly female skater working at a SoCal skate company who was upset by how cruelly she was being treated and shared disturbing stories about Gator. “I can’t reliably recall the details, and it’s her story to tell, but I do remember being unnerved by it. Less than a year later Gator confessed to brutally killing a young woman he knew. So, the story that young skater had told me was tragically proved to be grounded in reality” (2024).

As a result, Michelle felt disillusioned by the U.S., returned home and didn’t skate for a year. Fortunately, her friends back in Brighton (aka “Pig City”) coaxed her to step back on her board. Michelle was grateful that there were some countervailing activities to such violent behaviours. “Look at the photos of Stephanie Person doing big airs with a giant anti-racism sticker on her board right in the field of photographic view. And, as said, the UK’s Skateboard! magazine had made a point in 1989 of doing an all-women skate feature series, calling out the misogyny. The last two words of [Ian Lawton] Meany’s well written intro were: ‘F**k chauvinism’” (2024).

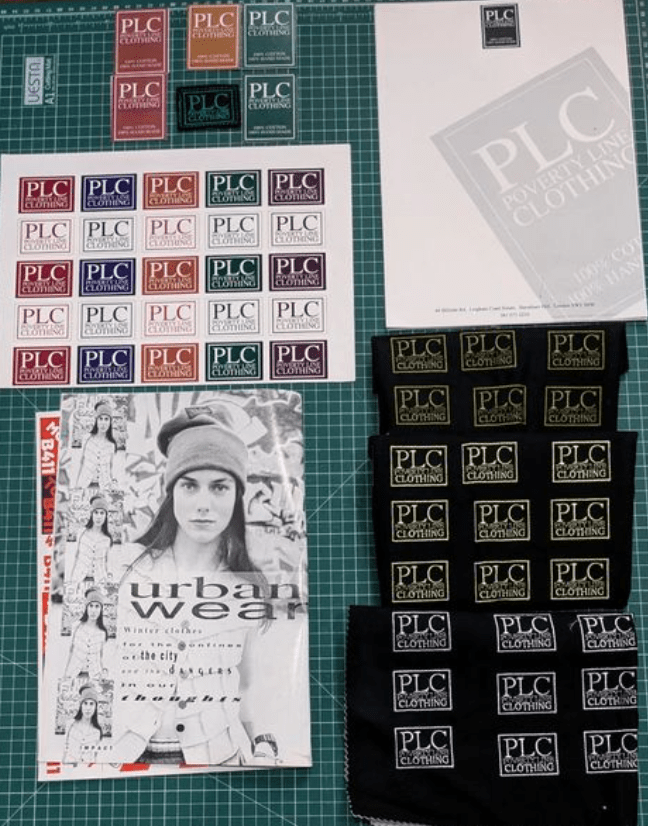

In the 1990s, Michelle decided to launch her own initiative called Poverty Line Clothing, which included hand-made fleece hats and pursue journalism. She stated that, “it would be fascinating to attempt to counteract the gender imbalances in the [skateboard industry] culture. The reason there is such a warped mentality is that there are so few females involved to even it out. The natural progression for me is snow boarding, but behind the scenes of magazines, films, sponsorship et al. The media is very competitive but you make a life out of what you are good at so we’ll see how I end up… I’ll still be skating, they won’t grind me down” (1994).

Photo: Michelle Ticktin’s PLC Clothing line circa 1993 from Instagram. Her hats were “sold in Slam City Skates in Covent Garden, Ellis Brigham’s around the corner and a boutique in Brighton Lanes.” Apparently Robin Williams even bought one!

Michelle shared that she continues to be friends with Teresa, her vert skating buddy from Brighton to this day. And she was encouraged by the progress of women in skateboarding, as seen at the Olympic Games.

“When I skated from the early 1980s to the early-mid 1990s, there wasn’t much of an interest in women’s skateboarding. In general, marketing cared about men’s skateboarding because that’s where the money was and competitions weren’t gender segmented. You can see now that people are enthusiastic about women’s skateboarding. There’s a competitive circuit for women and I suppose marketeers woke up to the sales potential. I can see that girl and women skaters have a degree of confidence and take it for granted that they have a place and a space to skate that’s theirs. Judging by the Olympics, women are skating fluidly and powerfully, maybe faster, maybe higher. They look relaxed. And I suspect they’re better protected.

I also see from a quick rummage around the interweb that women are putting up open opposition to misogyny, although it still seems to be a struggle. From what I can see – and I’m at a real distance from it now – it’s still a male-dominated activity and I do wonder about the diversity of coaching at the top tier for female competitors.

If women skaters are looking for inspiration, they could take it from the struggle within women’s gymnastics. Now, women own their own sport more than they ever have: they take pride in their capacities, they are proud of their bodies, and they take genuine joy in each other’s achievements. The moment of camaraderie when Simone Biles and Jordan Chiles kneeled to Rebecca Andrade on the podium at last summer’s Olympics was superb.”

Reference:

- Jones, Beth. “Michelle Ticktin.” Brighton Argus. August 1994.

- Ticktin, Michelle. Personal email. October 28, 2024.

- Welsh, Christian. “Michelle Picktin.” Skateboard! November 1989, pp. 22-23.